Sets¶

Definition of a Set¶

In mathematics, a set is a well-defined collection of distinct objects, considered as an object in its own right. The objects that make up a set are called its elements or members. The key characteristics of a set are:

- Well-defined: It must be clear and unambiguous whether an object belongs to the set or not. For example, "the set of tall students in a class" is not well-defined because "tall" is subjective. However, "the set of students in a class taller than 170 cm" is well-defined.

- Distinct: A set does not contain duplicate elements. Each element is unique.

- Unordered: The order in which elements are listed does not matter. The set \(\{a, b, c\}\) is the same as \(\{c, a, b\}\).

Notation

- Sets are usually denoted by capital letters (e.g., \(A, B, S\)).

- Elements are usually denoted by lowercase letters (e.g., \(a, b, x\)).

- If \(x\) is an element of a set \(A\), we write \(x \in A\) (read as "x belongs to A").

- If \(x\) is not an element of a set \(A\), we write \(x \notin A\) (read as "x does not belong to A").

Representation of Sets¶

There are two primary ways to represent a set:

-

Roster or Tabular Form: All the elements of the set are listed, separated by commas and enclosed within curly braces \(\{\}\).

Roster Form

- The set \(V\) of vowels in the English alphabet: \(V = \{a, e, i, o, u\}\)

- The set \(N\) of the first 5 natural numbers: \(N = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}\)

- The set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}\): \(\mathbb{Z} = \{\dots, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, \dots\}\)

-

Set-Builder or Rule Form: A set is described by stating a property that its elements must satisfy. The general form is \(A = \{x \mid P(x)\}\) or \(A = \{x : P(x)\}\), which is read as "the set of all elements \(x\) such that \(x\) satisfies the property \(P(x)\)".

Set-Builder Form

- The set \(V\) of vowels in the English alphabet: \(V = \{x \mid x \text{ is a vowel in the English alphabet}\}\)

- The set \(E\) of all even integers: \(E = \{x \mid x \in \mathbb{Z} \text{ and } x = 2k \text{ for some integer } k\}\)

- The set \(Q\) of rational numbers: \(Q = \{x \mid x = p/q, \text{ where } p, q \in \mathbb{Z} \text{ and } q \neq 0\}\)

Important Sets in Mathematics¶

- \(\emptyset\) or \(\{\}\): The empty set or null set, which contains no elements.

- \(\mathbb{N}\): The set of Natural Numbers \(\{1, 2, 3, \dots\}\).

- \(\mathbb{W}\): The set of Whole Numbers \(\{0, 1, 2, 3, \dots\}\).

- \(\mathbb{Z}\): The set of Integers \(\{\dots, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, \dots\}\).

- \(\mathbb{Q}\): The set of Rational Numbers (fractions).

- \(\mathbb{R}\): The set of Real Numbers (includes all rational and irrational numbers).

- \(\mathbb{C}\): The set of Complex Numbers.

Cardinality of a Set¶

The cardinality of a set is a measure of the "number of elements" of the set. For a finite set, the cardinality is simply the count of its elements.

Notation

The cardinality of a set \(A\) is denoted by \(|A|\), \(n(A)\), or \(card(A)\).

Cardinality

- If \(A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\}\), then \(|A| = 4\).

- If \(V = \{a, e, i, o, u\}\), then \(|V| = 5\).

- For the empty set, \(|\emptyset| = 0\).

- For the set \(B = \{a, b, \{c, d\}\}\), \(|B| = 3\). The elements are \(a\), \(b\), and the set \(\{c, d\}\).

Classification of Sets¶

Based on their cardinality, sets can be classified into finite, countable, and infinite.

Finite Sets¶

A set is called finite if it is either empty or contains a specific, countable number of elements. In other words, if the process of counting its elements can eventually come to an end.

Formally, a set \(S\) is finite if there exists a one-to-one correspondence (a bijection) between its elements and the set \(\{1, 2, 3, \dots, n\}\) for some non-negative integer \(n\). The cardinality of such a set is \(|S| = n\).

Finite Sets

- The set of days in a week: \(|\{\text{Sun, Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat}\}| = 7\).

- The set of students in your classroom.

- The set of all prime numbers less than 100.

Infinite Sets¶

A set that is not finite is called an infinite set. The process of counting its elements would never end.

Infinite Sets

- The set of natural numbers \(\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, \dots\}\).

- The set of all points on a line.

- The set of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\).

Infinite sets can be further divided into two categories: countable and uncountable.

Countable Sets¶

A set is countable if its elements can be put into a one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers \(\mathbb{N}\). This essentially means we can "list" all the elements of the set in a sequence \(a_1, a_2, a_3, \dots\), even if the list goes on forever.

- All finite sets are countable.

- An infinite set that is countable is called countably infinite or denumerable.

The cardinality of a countably infinite set is denoted by the symbol \(\aleph_0\) (aleph-null). Thus, \(|\mathbb{N}| = \aleph_0\).

Key Countably Infinite Sets

- The Set of Natural Numbers (\(\mathbb{N}\)): This is the fundamental example of a countably infinite set. \(|\mathbb{N}| = \aleph_0\).

- The Set of Integers (\(\mathbb{Z}\)): This set is also countably infinite. We can list its elements like this: \(0, 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, \dots\). This ensures every integer appears exactly once in the list. So, \(|\mathbb{Z}| = \aleph_0\).

- The Set of Rational Numbers (\(\mathbb{Q}\)): Surprisingly, the set of all fractions is also countably infinite. Although they seem much more "dense" than integers, it can be proven that they can be systematically listed without missing any. So, \(|\mathbb{Q}| = \aleph_0\).

Uncountable Sets¶

An infinite set that is not countable is called an uncountable set (or uncountably infinite). It is impossible to list all the elements of an uncountable set in a sequence. These sets are "larger" in size than countably infinite sets.

Uncountable Sets are 'Bigger' Infinities

The existence of uncountable sets implies that there are different sizes of infinity. The cardinality of countably infinite sets (\(\aleph_0\)) is the "smallest" infinity.

Uncountable Sets

- The Set of Real Numbers (\(\mathbb{R}\)): This is the most common example of an uncountable set. The famous Cantor's diagonalization argument proves that the real numbers between 0 and 1 alone cannot be put into a one-to-one correspondence with \(\mathbb{N}\). Therefore, the set of all real numbers is uncountable. Its cardinality is denoted by \(c\) (for continuum) or \(\aleph_1\). We know that \(\aleph_0 < c\).

- The Power Set of \(\mathbb{N}\): The set of all subsets of the natural numbers, denoted \(P(\mathbb{N})\), is also uncountable.

Summary Table¶

| Category | Definition | Cardinality | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finite | Empty or has \(n\) elements for some \(n \in \mathbb{W}\). | ( | A |

| Infinite | Not finite. | Infinite | \(\mathbb{N}, \mathbb{Z}, \mathbb{Q}, \mathbb{R}\) |

| Countably Infinite | Can be put in 1-to-1 correspondence with \(\mathbb{N}\). | ( | A |

| Uncountably Infinite | Cannot be put in 1-to-1 correspondence with \(\mathbb{N}\). | ( | A |

Operations on Sets and Venn Diagrams¶

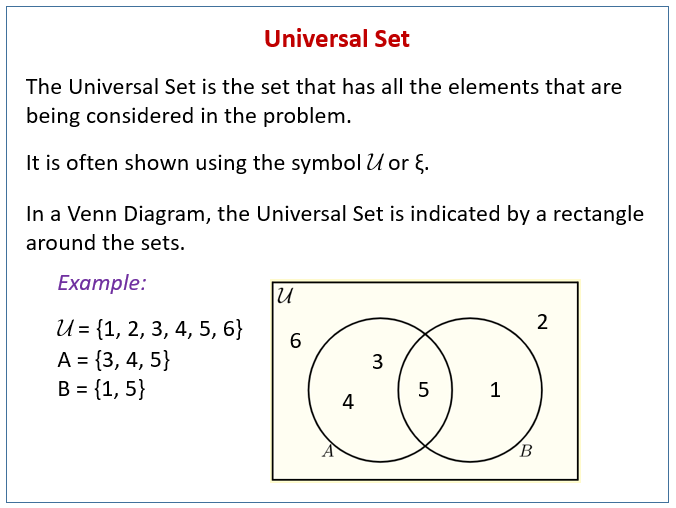

Universal Set (U)¶

Before diving into operations, it's crucial to understand the Universal Set, denoted by \(U\). The universal set is the set containing all possible elements under consideration for a particular problem. All other sets are considered subsets of the universal set.

- Example: If we are discussing sets of vowels, the universal set could be \(U = \{a, e, i, o, u\}\). If we are discussing sets of single-digit numbers, \(U = \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\}\).

Venn Diagrams¶

A Venn diagram is a visual representation of the relationship between sets. It uses overlapping circles or other shapes to illustrate the logical relationships between two or more sets. The universal set is typically represented by a rectangle, and subsets are represented by circles within this rectangle.

Basic Set Operations¶

Let's consider two sets, \(A\) and \(B\), which are subsets of a universal set \(U\).

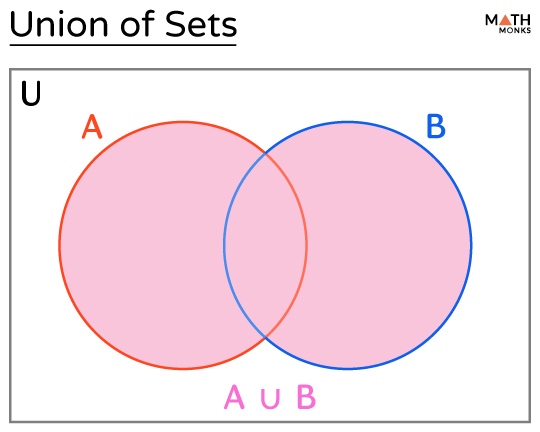

Union of Sets (∪)¶

The union of two sets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted by \(A \cup B\), is the set of all elements that are in set \(A\), or in set \(B\), or in both.

- Set-Builder Notation: \(A \cup B = \{x \mid x \in A \lor x \in B\}\)

- Explanation: It combines all unique elements from both sets.

- Example:

- Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{3, 4, 5\}\).

- Then, \(A \cup B = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}\).

Venn Diagram for Union¶

The union is represented by shading the entire area covered by both circles \(A\) and \(B\).

Intersection of Sets (∩)¶

The intersection of two sets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted by \(A \cap B\), is the set of all elements that are common to both set \(A\) and set \(B\).

- Set-Builder Notation: \(A \cap B = \{x \mid x \in A \land x \in B\}\)

- Explanation: It includes only the elements that exist in both sets simultaneously.

- Example:

- Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{3, 4, 5\}\).

- Then, \(A \cap B = \{3\}\).

If \(A \cap B = \emptyset\) (the empty set), then \(A\) and \(B\) are called disjoint sets.

Venn Diagram for Intersection¶

The intersection is represented by shading only the overlapping area of circles \(A\) and \(B\).

Difference of Sets (− or \)¶

The difference between two sets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted by \(A - B\) or \(A \setminus B\), is the set of all elements that are in set \(A\) but not in set \(B\).

- Set-Builder Notation: \(A - B = \{x \mid x \in A \land x \notin B\}\)

- Explanation: Start with set \(A\) and remove all elements that are also present in set \(B\). Note that \(A - B \neq B - A\) in general.

- Example:

- Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{3, 4, 5\}\).

- Then, \(A - B = \{1, 2\}\).

- And, \(B - A = \{4, 5\}\).

Venn Diagram for Difference¶

The difference \(A - B\) is represented by shading the area of circle \(A\) that does not overlap with circle \(B\).

Complement of a Set (A' or Aᶜ)¶

The complement of a set \(A\), denoted by \(A'\) or \(A^c\), is the set of all elements in the universal set \(U\) that are not in set \(A\).

- Set-Builder Notation: \(A' = \{x \in U \mid x \notin A\}\)

- Explanation: It's essentially \(U - A\).

- Example:

- Let \(U = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\) and \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\).

- Then, \(A' = \{4, 5, 6\}\).

Venn Diagram for Complement¶

The complement of \(A\) is represented by shading the area inside the universal set's rectangle but outside the circle \(A\).

Symmetric Difference (Δ or ⊕)¶

The symmetric difference of two sets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted by \(A \Delta B\), is the set of all elements that are in either of the sets, but not in their intersection.

- Set-Builder Notation: \(A \Delta B = \{x \mid (x \in A \land x \notin B) \lor (x \in B \land x \notin A)\}\)

- Relationship with other operations:

- \(A \Delta B = (A - B) \cup (B - A)\)

- \(A \Delta B = (A \cup B) - (A \cap B)\)

- Example:

- Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{3, 4, 5\}\).

- \(A \cup B = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}\)

- \(A \cap B = \{3\}\)

- Then, \(A \Delta B = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} - \{3\} = \{1, 2, 4, 5\}\).

Venn Diagram for Symmetric Difference¶

The symmetric difference is represented by shading all parts of circles \(A\) and \(B\) except for their overlapping intersection.

Laws of Set Algebra¶

Just like algebra with numbers, set operations follow certain laws.

| Law | Union | Intersection |

|---|---|---|

| Commutative Law | \(A \cup B = B \cup A\) | \(A \cap B = B \cap A\) |

| Associative Law | \((A \cup B) \cup C = A \cup (B \cup C)\) | \((A \cap B) \cap C = A \cap (B \cap C)\) |

| Distributive Law | \(A \cup (B \cap C) = (A \cup B) \cap (A \cup C)\) | \(A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)\) |

| Identity Law | \(A \cup \emptyset = A\) | \(A \cap U = A\) |

| Complement Law | \(A \cup A' = U\) | \(A \cap A' = \emptyset\) |

| Idempotent Law | \(A \cup A = A\) | \(A \cap A = A\) |

De Morgan's Laws¶

De Morgan's laws are two fundamental rules that relate union, intersection, and complementation.

-

First Law: The complement of the union of two sets is the intersection of their complements.

- \((A \cup B)' = A' \cap B'\)

-

Second Law: The complement of the intersection of two sets is the union of their complements.

- \((A \cap B)' = A' \cup B'\)

Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion¶

The Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion (PIE) is a fundamental counting technique in combinatorics. It provides a systematic way to find the number of elements in the union of multiple sets by adding the sizes of the individual sets and then compensating for the elements that have been counted multiple times.

The core idea is to "include" the sizes of the individual sets, then "exclude" the sizes of their pairwise intersections, then "include" the sizes of their three-way intersections, and so on, with alternating signs.

PIE for Two Sets¶

For two finite sets, \(A\) and \(B\), the number of elements in their union \(A \cup B\) is the sum of the number of elements in each set minus the number of elements in their intersection.

The formula is:

- \(|A|\): The cardinality (number of elements) of set A.

- \(|B|\): The cardinality of set B.

- \(|A \cap B|\): The cardinality of the intersection of A and B (elements common to both).

We subtract \(|A \cap B|\) because these elements were counted twice: once in \(|A|\) and once in \(|B|\).

Example: Students and Subjects

In a class of 50 students, 30 students passed in Mathematics (\(M\)), 25 passed in Science (\(S\)), and 15 passed in both subjects. How many students passed in at least one of the two subjects?

- Let \(M\) be the set of students who passed in Mathematics, so \(|M| = 30\).

- Let \(S\) be the set of students who passed in Science, so \(|S| = 25\).

- The set of students who passed in both is \(M \cap S\), so \(|M \cap S| = 15\).

We want to find the number of students who passed in at least one subject, which is \(|M \cup S|\).

Using the Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion: [ |M \cup S| = |M| + |S| - |M \cap S| ] [ |M \cup S| = 30 + 25 - 15 = 40 ] Therefore, 40 students passed in at least one of the two subjects.

PIE for Three Sets¶

For three finite sets, \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\), the principle is extended. We add the sizes of the sets, subtract the sizes of all pairwise intersections, and finally add back the size of the three-way intersection.

The formula is:

- Inclusion: We first add \(|A|\), \(|B|\), and \(|C|\). This overcounts elements in the intersections.

- Exclusion: We subtract \(|A \cap B|\), \(|A \cap C|\), and \(|B \cap C|\) to correct for the double-counting. However, this over-corrects for the elements in \(A \cap B \cap C\), which were initially counted three times and have now been subtracted three times.

- Inclusion: We add back \(|A \cap B \cap C|\) to ensure these elements are counted exactly once.

The General Principle¶

The principle can be generalized to find the cardinality of the union of \(n\) finite sets, \(A_1, A_2, \dots, A_n\).

The general formula is:

In a more compact summation notation:

Complementary Form

Often, we are interested in finding the number of elements that are in none of the sets. If \(U\) is the universal set, this is given by \(|\overline{A_1} \cap \overline{A_2} \cap \dots \cap \overline{A_n}|\). By De Morgan's laws, this is equal to \(|\overline{A_1 \cup A_2 \cup \dots \cup A_n}|\).

Applications of PIE¶

The Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion has several important applications in combinatorics and number theory.

Counting Integers with Specific Properties¶

PIE is used to count the number of integers in a range that are divisible by a certain set of numbers.

Example: Divisibility

How many positive integers not exceeding 1000 are divisible by 5, 7, or 11?

- Universal Set: \(U = \{1, 2, \dots, 1000\}\), so \(|U|=1000\).

-

Sets:

- Let \(A\) be the set of integers divisible by 5. \(|A| = \lfloor \frac{1000}{5} \rfloor = 200\).

- Let \(B\) be the set of integers divisible by 7. \(|B| = \lfloor \frac{1000}{7} \rfloor = 142\).

- Let \(C\) be the set of integers divisible by 11. \(|C| = \lfloor \frac{1000}{11} \rfloor = 90\).

-

Pairwise Intersections (divisible by pairs of numbers):

- \(|A \cap B|\) (divisible by 5 and 7, i.e., 35): \( \lfloor \frac{1000}{35} \rfloor = 28\).

- \(|A \cap C|\) (divisible by 5 and 11, i.e., 55): \( \lfloor \frac{1000}{55} \rfloor = 18\).

- \(|B \cap C|\) (divisible by 7 and 11, i.e., 77): \( \lfloor \frac{1000}{77} \rfloor = 12\).

-

Three-way Intersection (divisible by 5, 7, and 11, i.e., 385):

- \(|A \cap B \cap C|\): \( \lfloor \frac{1000}{385} \rfloor = 2\).

-

Applying PIE:

So, 376 integers not exceeding 1000 are divisible by 5, 7, or 11.

Derangements¶

A derangement is a permutation of the elements of a set such that no element appears in its original position. The number of derangements of \(n\) elements is denoted by \(D_n\) or \(!n\).

- Problem: Find the number of derangements of \(n\) objects.

- Approach: We find the total number of permutations (\(n!\)) and subtract the number of permutations where at least one element is in its correct place.

Let \(U\) be the set of all \(n!\) permutations. Let \(A_i\) be the set of permutations where the \(i\)-th element is in its original position. We want to find the number of permutations that are in none of these sets, i.e., \(|U| - |A_1 \cup A_2 \cup \dots \cup A_n|\).

- The size of \(A_i\) is \((n-1)!\) (fix element \(i\) and permute the other \(n-1\)). There are \(\binom{n}{1}\) such sets.

- The size of \(A_i \cap A_j\) is \((n-2)!\). There are \(\binom{n}{2}\) such intersections.

- The size of a \(k\)-wise intersection is \((n-k)!\). There are \(\binom{n}{k}\) such intersections.

Using PIE, the number of permutations with at least one fixed point is:

Simplifying \(\binom{n}{k}(n-k)! = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}(n-k)! = \frac{n!}{k!}\), we get:

The number of derangements \(D_n\) is:

Number of Surjective (Onto) Functions¶

A function \(f: A \to B\) is surjective (or onto) if every element in the codomain \(B\) is an image of at least one element from the domain \(A\). PIE can be used to count the number of such functions.

- Problem: Find the number of surjective functions from set \(A\) with \(m\) elements to set \(B\) with \(n\) elements, where \(m \ge n\).

- Approach: Start with the total number of functions from \(A\) to \(B\), which is \(n^m\). Then, subtract the functions that are not surjective. A function is not surjective if at least one element in \(B\) is not in the image.

Let \(B = \{b_1, b_2, \dots, b_n\}\). Let \(A_i\) be the set of functions where the element \(b_i \in B\) is not in the image of the function. We want to find the number of functions that are in none of these sets, which is \(n^m - |A_1 \cup A_2 \cup \dots \cup A_n|\).

- The size of \(A_i\): These are functions from \(A\) to \(B - \{b_i\}\). There are \((n-1)\) choices in the codomain for each of the \(m\) elements in the domain. So, \(|A_i| = (n-1)^m\).

- The size of \(A_i \cap A_j\): These are functions that miss both \(b_i\) and \(b_j\). So, \(|A_i \cap A_j| = (n-2)^m\).

- The size of a \(k\)-wise intersection is \((n-k)^m\).

The number of functions that are not surjective is \(|A_1 \cup \dots \cup A_n|\):

The number of surjective functions is:

This simplifies to the formula:

Multisets¶

A multiset is a modification of the concept of a set that, unlike a standard set, allows for multiple instances of each of its elements. The number of times an element appears in a multiset is called its multiplicity. Multisets are also sometimes called bags.

For example, \(\{1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3\}\) and \(\{a, b, b, c, d, d, d\}\) are multisets. In a standard set, these would be represented as \(\{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(\{a, b, c, d\}\), respectively, as duplicates are not counted.

Formal Definition¶

Formally, a multiset \(M\) can be defined as an ordered pair \((S, m)\), where \(S\) is the underlying set of distinct elements, and \(m\) is a multiplicity function \(m: S \to \mathbb{Z}^+\), which maps each element in \(S\) to a positive integer representing its multiplicity.

For the multiset \(M = \{a, a, b, c, c, c\}\):

- The underlying set is \(S = \{a, b, c\}\).

- The multiplicity function \(m\) is defined as:

- \(m(a) = 2\)

- \(m(b) = 1\)

- \(m(c) = 3\)

Cardinality of a Multiset¶

The cardinality (or size) of a multiset is the total number of elements it contains, including repetitions. It is the sum of the multiplicities of all its distinct elements.

If \(M = (S, m)\) is a multiset, its cardinality, denoted as \(|M|\) or \(card(M)\), is calculated as: [ |M| = \sum_{x \in S} m(x) ] Example: For the multiset \(M = \{1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4\}\):

- Underlying set \(S = \{1, 2, 3, 4\}\).

- Multiplicities are \(m(1)=2\), \(m(2)=1\), \(m(3)=3\), \(m(4)=1\).

- The cardinality is \(|M| = 2 + 1 + 3 + 1 = 7\).

Submultisets¶

A multiset \(A\) is a submultiset of a multiset \(B\), denoted \(A \subseteq B\), if the multiplicity of each element in \(A\) is less than or equal to its multiplicity in \(B\).

Formally, let \(A = (S_A, m_A)\) and \(B = (S_B, m_B)\). Then \(A \subseteq B\) if and only if for every element \(x \in S_A\), \(x\) is also in \(S_B\) and \(m_A(x) \le m_B(x)\).

Example: If \(A = \{a, a, b\}\) and \(B = \{a, a, a, b, c\}\), then \(A\) is a submultiset of \(B\) because:

- \(m_A(a) = 2\) and \(m_B(a) = 3\), so \(2 \le 3\).

- \(m_A(b) = 1\) and \(m_B(b) = 1\), so \(1 \le 1\).

Operations on Multisets¶

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two multisets. Let \(m_A(x)\) and \(m_B(x)\) be the multiplicities of an element \(x\) in \(A\) and \(B\) respectively. (If an element is not in a multiset, its multiplicity is 0).

Union¶

The union of two multisets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted \(A \cup B\), is a multiset where the multiplicity of an element is the maximum of its multiplicities in \(A\) and \(B\). [ m_{A \cup B}(x) = \max(m_A(x), m_B(x)) ] Example: Let \(A = \{1, 1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{1, 2, 2, 4\}\).

- \(m_A(1) = 2\), \(m_B(1) = 1 \implies \max(2, 1) = 2\). Multiplicity of 1 is 2.

- \(m_A(2) = 1\), \(m_B(2) = 2 \implies \max(1, 2) = 2\). Multiplicity of 2 is 2.

- \(m_A(3) = 1\), \(m_B(3) = 0 \implies \max(1, 0) = 1\). Multiplicity of 3 is 1.

- \(m_A(4) = 0\), \(m_B(4) = 1 \implies \max(0, 1) = 1\). Multiplicity of 4 is 1.

Therefore, \(A \cup B = \{1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4\}\).

Intersection¶

The intersection of two multisets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted \(A \cap B\), is a multiset where the multiplicity of an element is the minimum of its multiplicities in \(A\) and \(B\). [ m_{A \cap B}(x) = \min(m_A(x), m_B(x)) ] Example: Let \(A = \{1, 1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{1, 2, 2, 4\}\).

- \(m_A(1) = 2\), \(m_B(1) = 1 \implies \min(2, 1) = 1\). Multiplicity of 1 is 1.

- \(m_A(2) = 1\), \(m_B(2) = 2 \implies \min(1, 2) = 1\). Multiplicity of 2 is 1.

- \(m_A(3) = 1\), \(m_B(3) = 0 \implies \min(1, 0) = 0\). Multiplicity of 3 is 0.

- \(m_A(4) = 0\), \(m_B(4) = 1 \implies \min(0, 1) = 0\). Multiplicity of 4 is 0.

Therefore, \(A \cap B = \{1, 2\}\).

Sum¶

The sum of two multisets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted \(A + B\) or \(A \uplus B\), is a multiset where the multiplicity of an element is the sum of its multiplicities in \(A\) and \(B\). This operation is also known as the disjoint union. [ m_{A+B}(x) = m_A(x) + m_B(x) ] Example: Let \(A = \{a, b, b\}\) and \(B = \{b, c\}\).

- \(m_A(a) = 1\), \(m_B(a) = 0 \implies 1 + 0 = 1\). Multiplicity of \(a\) is 1.

- \(m_A(b) = 2\), \(m_B(b) = 1 \implies 2 + 1 = 3\). Multiplicity of \(b\) is 3.

- \(m_A(c) = 0\), \(m_B(c) = 1 \implies 0 + 1 = 1\). Multiplicity of \(c\) is 1.

Therefore, \(A + B = \{a, b, b, b, c\}\).

Difference¶

The difference of two multisets \(A\) and \(B\), denoted \(A - B\), is a multiset where the multiplicity of an element \(x\) in \(A - B\) is the multiplicity of \(x\) in \(A\) minus its multiplicity in \(B\), if the result is positive. Otherwise, the multiplicity is 0. [ m_{A-B}(x) = \max(0, m_A(x) - m_B(x)) ] Example: Let \(A = \{1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3\}\) and \(B = \{1, 1, 3, 4\}\).

- For element 1: \(m_A(1) - m_B(1) = 3 - 2 = 1\).

- For element 2: \(m_A(2) - m_B(2) = 1 - 0 = 1\).

- For element 3: \(m_A(3) - m_B(3) = 2 - 1 = 1\).

- For element 4: \(m_A(4) - m_B(4) = 0 - 1 = -1\). Since this is negative, the multiplicity is \(\max(0, -1) = 0\).

Therefore, \(A - B = \{1, 2, 3\}\).

Applications of Multisets¶

Multisets are useful in various fields of mathematics and computer science.

- Prime Factorization: The prime factorization of an integer is a multiset of prime numbers. For example, the factorization of 120 is \(2^3 \cdot 3^1 \cdot 5^1\), which corresponds to the multiset \(\{2, 2, 2, 3, 5\}\).

- Combinatorics: Multisets are used in counting problems, particularly for calculating permutations and combinations where repetitions are allowed. The number of permutations of a multiset of size \(n\) is given by the multinomial coefficient.

- Computer Science:

- In database systems, query results can often be multisets (bags) rather than sets, as duplicate rows might be returned.

- In data structures, a "bag" is an abstract data type that implements the multiset concept.

- Frequency analysis in text processing or data mining relies on counting occurrences, which is a multiset concept.

Problem Set¶

This problem set covers fundamental concepts of set theory, including operations, the Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion, and multisets, designed for Bachelor of Computer Applications (BCA) students.

Basics of Sets¶

- Represent the set \(A = \{x | x \text{ is an integer and } -3 < x \le 4\}\) in Roster form.

- Represent the set \(B = \{1, 4, 9, 16, 25, \dots\}\) in Set-builder notation.

- Which of the following are well-defined sets? Justify your answer.

- The collection of all intelligent students in a class.

- The collection of all prime numbers less than 100.

- The collection of all beautiful flowers in a garden.

- If \(S\) is the set of letters in the word "DISCRETE", write \(S\) in Roster form. What is the cardinality of \(S\)?

- Let \(\mathbb{N}\) be the set of natural numbers. Describe the set \(C = \{x \in \mathbb{N} | x = 2k \text{ for some } k \in \mathbb{N}\}\) in words.

- Find the cardinality of the set \(A = \{x \in \mathbb{Z} | x^2 - 9 = 0\}\).

- If a set \(A\) has 5 elements, what is the cardinality of its power set, \(|P(A)|\)?

- Let \(A\) be the set of all functions from \(\{1, 2\}\) to \(\{a, b\}\). List all the elements of \(A\).

- Classify the following sets as finite, countably infinite, or uncountably infinite:

- The set of all atoms in the universe.

- The set of all rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\).

- The set of all real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\) between 0 and 1.

- The set of all lines in a plane.

- Prove that the set of all integers, \(\mathbb{Z}\), is countably infinite by defining a bijective function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}\).

- Explain why the set of all bit strings (strings of 0s and 1s) is countably infinite.

- Give an informal argument (e.g., Cantor's diagonalization) to explain why the power set of natural numbers, \(P(\mathbb{N})\), is uncountable.

- Is the set of all computer programs that can be written in Python finite, countably infinite, or uncountably infinite? Justify your reasoning.

- Let \(A_i = \{i, i+1, i+2, \dots\}\) for \(i \in \mathbb{N}\). What is \(\bigcap_{i=1}^{\infty} A_i\)?

- What is the cardinality of the Cartesian product of the set of vowels and the set of consonants in the English alphabet?

Operations on Sets and Venn Diagrams¶

- Let \(U = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10\}\), \(A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}\), \(B = \{4, 5, 6, 7\}\), and \(C = \{5, 6, 8, 9\}\). Find:

- \(A \cup B\)

- \(A \cap C\)

- \(B - C\)

- \(A^c\)

- \(A \Delta B\)

- Draw a Venn diagram for three sets A, B, and C, and shade the region corresponding to \((A \cup B) \cap C\).

- Draw a Venn diagram to represent \(A - (B \cup C)\).

- If \(|A| = 15\), \(|B| = 20\), and \(|A \cup B| = 30\), find \(|A \cap B|\).

- If \(A \subseteq B\), what are \(A \cup B\), \(A \cap B\), and \(A - B\)?

- Prove the distributive law \(A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)\) using a membership table.

- Prove De Morgan's Law, \((A \cap B)^c = A^c \cup B^c\), using set builder notation and logical equivalences.

- Using the laws of set algebra, simplify the expression: \((A \cup B) \cap (A \cup B^c)\).

- Prove that for any sets A and B, \(A - B = A \cap B^c\).

- Prove the Absorption Law, \(A \cup (A \cap B) = A\), using set algebra laws.

- If \(A \Delta C = B \Delta C\), prove that \(A=B\). (Hint: Use the property \(X \Delta X = \emptyset\)).

- For any two sets \(A\) and \(B\), show that \(P(A) \cup P(B) \subseteq P(A \cup B)\). Is the reverse inclusion, \(P(A \cup B) \subseteq P(A) \cup P(B)\), always true? Provide a counterexample if not.

- Let \(A, B, C\) be sets. Prove that \((A - B) - C = A - (B \cup C)\).

- Describe the symmetric difference \(A \Delta B\) in terms of union, intersection, and complement. Shade the corresponding region in a Venn diagram.

- Let \(A = \{ \emptyset, \{\emptyset\} \}\). Find the power set \(P(A)\).

- Simplify the set expression \([(A' \cup B')' \cup (A' \cup B)']'\).

- What can you say about sets A and B if \(A - B = A\)?

- What can you say about sets A and B if \(A - B = B - A\)?

- Prove or disprove: If \(A \cup C = B \cup C\), then \(A = B\).

- Prove using set algebra that \((A \cap B) \cup (A - B) = A\).

Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion (PIE)¶

- In a survey of 200 students, 120 study Chemistry, 100 study Physics, and 30 study neither. How many students study both Chemistry and Physics?

- Find the number of integers between 1 and 500 (inclusive) that are divisible by 3 or 5.

- A survey of 100 coffee drinkers found that 70 take sugar, 60 take cream, and 50 take both. How many take either sugar or cream? How many take neither?

- In a group of students, 150 are enrolled in Mathematics, 100 in Physics, and 80 in Chemistry. Also, 60 are in Mathematics and Physics, 50 in Physics and Chemistry, and 70 in Mathematics and Chemistry. 30 students are enrolled in all three courses. Find the total number of students in the group, assuming every student is in at least one course.

- Use the Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion to find the number of positive integers less than or equal to 100 that are not divisible by 2, 3, or 5.

- State the general formula for the Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion for four sets: \(|A \cup B \cup C \cup D|\).

- How many permutations of the set \(\{1, 2, 3, 4\}\) leave no element in its original position? (i.e., find the number of derangements \(D_4\)).

- A manager has 6 tasks to assign to 6 employees. In how many ways can the tasks be assigned so that no employee gets the task they are supposed to get (as per their job description)? Calculate \(D_6\).

- State the formula for the number of surjective (onto) functions from a set \(A\) with \(m\) elements to a set \(B\) with \(n\) elements.

- Find the number of onto functions from a set with 6 elements to a set with 3 elements.

- How many ways are there to distribute 5 distinct balls into 3 distinct bins such that no bin is left empty?

- How many bit strings of length 8 do not contain the substring "11"? (This is a more advanced application, can be solved with PIE or recurrence relations).

- Find the number of integers between 1 and 1000 that are divisible by 7 but not by 11.

- How many integers from 1 to 300 are divisible by at least one of 2, 3, 5?

- How many solutions does the equation \(x_1 + x_2 + x_3 = 11\) have, where \(x_1, x_2, x_3\) are non-negative integers such that \(x_1 \le 3\), \(x_2 \le 4\), and \(x_3 \le 6\)? (Hint: Use PIE with upper bounds).

Multisets¶

- Define a multiset formally using a multiplicity function. Provide an example of a multiset with cardinality 8 and 4 distinct elements.

- Let \(M = \{a, b, b, c, c, c, d, d\}\).

- What is the cardinality of M?

- List all submultisets of M with cardinality 3.

- Let \(A = \{1, 1, 2, 3, 5\}\) and \(B = \{1, 2, 2, 4, 5\}\) be two multisets. Find:

- \(A \cup B\) (Union)

- \(A \cap B\) (Intersection)

- \(A + B\) (Sum)

- \(A - B\) (Difference)

- Explain the key difference between the union (\(\cup\)) and sum (\(+\)) operations on multisets. If \(A = \{a, b\}\) and \(B = \{a, c\}\), calculate \(A \cup B\) and \(A + B\).

- Let \(M_1\) and \(M_2\) be multisets drawn from a universal set \(U\). If \(k_1(x)\) and \(k_2(x)\) are the multiplicities of an element \(x\) in \(M_1\) and \(M_2\) respectively, define the multiplicity of \(x\) in \(M_1 \cup M_2\) and \(M_1 \cap M_2\).

- Find the number of 5-element multisets that can be formed from the set \(\{a, b, c, d\}\). (This is equivalent to combinations with repetition).

- In how many ways can a bakery sell a dozen (12) donuts if they offer 5 different varieties?

- Find the number of non-negative integer solutions to the equation \(x_1 + x_2 + x_3 + x_4 = 20\). Explain the connection between this problem and multisets.

- Find the number of integer solutions to \(y_1 + y_2 + y_3 = 10\) where \(y_i \ge 1\) for all \(i\). (Hint: Make a substitution).

- Let \(A\) be a multiset with \(k\) distinct elements and infinite copies of each. How many submultisets of size \(r\) does \(A\) have? Give the formula.