Relations¶

In discrete mathematics, a relation is a fundamental concept used to describe a relationship between elements of sets. It formalizes the idea that certain elements are connected or related to each other in some way.

Definition and Properties of Binary Relations¶

A binary relation from a set \(A\) to a set \(B\) is a collection of ordered pairs \((a, b)\) where \(a\) is an element of \(A\) and \(b\) is an element of \(B\). Essentially, it's a subset of the Cartesian product \(A \times B\).

If a relation is from a set \(A\) to itself (i.e., a subset of \(A \times A\)), it is called a relation on the set A.

Notation: If an ordered pair \((a, b)\) is in A relation \(R\), we write \((a, b) \in R\) or \(aRb\). This is read as "\(a\) is related to \(b\) by \(R\)".

Domain: The set of all first elements of the ordered pairs in \(R\).

Range: The set of all second elements of the ordered pairs in \(R\).

Example

Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{x, y, z\}\). Let \(R = \{(1, x), (1, y), (3, x)\}\) be a relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

- Here, \(1Rx\) and \(3Rx\) are true.

- The Domain of \(R\) is \(\{1, 3\}\).

- The Range of \(R\) is \(\{x, y\}\).

Representation of Relations¶

Relations can be represented in several ways:

Set-Roster Notation: Listing all the ordered pairs, as seen in the example above.

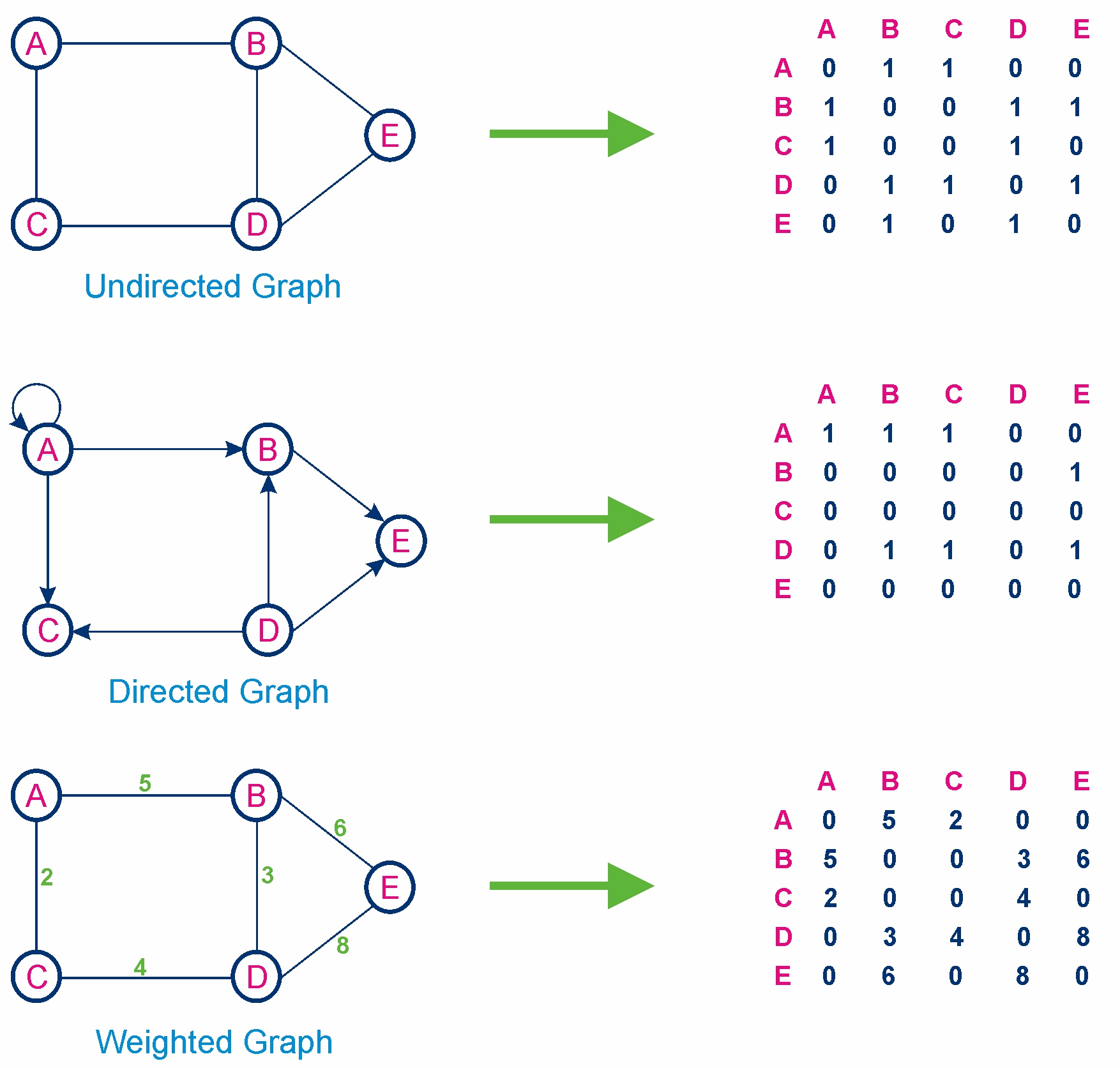

Matrix Representation: A relation \(R\) from \(A = \{a_1, ..., a_m\}\) to \(B = \{b_1, ..., b_n\}\) can be represented by an \(m \times n\) matrix \(M_R = [m_{ij}]\).

Directed Graph (Digraph): For a relation on a set \(A\), we can draw a digraph. Each element of \(A\) is a vertex. A directed edge is drawn from vertex \(a\) to vertex \(b\) if and only if \((a, b) \in R\). A loop (an edge from a vertex to itself) is drawn if \((a, a) \in R\).

Properties of Binary Relations¶

Let \(R\) be a binary relation on a set \(A\).

Reflexive¶

A relation \(R\) is reflexive if every element is related to itself.

- Matrix: All diagonal elements are 1.

- Digraph: Every vertex has a self-loop.

Example

The relation "is less than or equal to" (\(\le\)) on the set of integers is reflexive because every integer is less than or equal to itself (\(a \le a\)).

Irreflexive¶

A relation \(R\) is irreflexive if no element is related to itself.

- Matrix: All diagonal elements are 0.

- Digraph: No vertex has a self-loop.

Example

The relation "is greater than" (\(>\)) on the set of integers is irreflexive because no integer is greater than itself (\(a \not> a\)).

Symmetric¶

A relation \(R\) is symmetric if for every pair \((a, b)\) in the relation, the pair \((b, a)\) is also in the relation.

- Matrix: The matrix is symmetric about the main diagonal (\(M_R = M_R^T\)).

- Digraph: If there is an edge from \(a\) to \(b\), there must be an edge from \(b\) to \(a\).

Example

The relation "is equal to" (\(=\)) on integers is symmetric. If \(a = b\), then \(b = a\). A relation \(R = \{(1,2), (2,1), (3,3)\}\) on \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) is symmetric.

Antisymmetric¶

A relation \(R\) is antisymmetric if for any two distinct elements \(a\) and \(b\), it's not possible to have both \(a\) related to \(b\) and \(b\) related to \(a\).

- Matrix: If \(m_{ij} = 1\) for \(i \ne j\), then \(m_{ji}\) must be 0.

- Digraph: There cannot be edges in both directions between two distinct vertices.

Example

The relation "is less than or equal to" (\(\le\)) on integers is antisymmetric. If \(a \le b\) and \(b \le a\), it must be that \(a = b\). The relation "divides" on the set of positive integers is another example.

Asymmetric¶

A relation \(R\) is asymmetric if whenever \(a\) is related to \(b\), \(b\) is NOT related to \(a\).

Note

An asymmetric relation is both antisymmetric and irreflexive.

Example

The relation "is greater than" (\(>\)) on integers is asymmetric. If \(a > b\), then \(b \not> a\).

Transitive¶

A relation \(R\) is transitive if a "chain" of relations implies a direct relation.

- Matrix: If the Boolean product \(M_R \odot M_R\) has a 1 in position \((i, k)\), then \(M_R\) must also have a 1 in that position.

- Digraph: If there is a path of length 2 from vertex \(a\) to \(c\) (through some vertex \(b\)), then there must be a direct edge from \(a\) to \(c\).

Example

The relation "is an ancestor of" is transitive. If Ram is an ancestor of Shyam, and Shyam is an ancestor of Mohan, then Ram is an ancestor of Mohan. The relation \( \le \) on integers is also transitive. If \(a \le b\) and \(b \le c\), then \(a \le c\).

Closures of Relations¶

The closure of a relation \(R\) with respect to a property \(P\) is the smallest relation that contains \(R\) and satisfies property \(P\). "Smallest" means we add the minimum number of ordered pairs to \(R\) to achieve the property.

Reflexive Closure¶

The reflexive closure of a relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is the smallest reflexive relation containing \(R\). It is obtained by adding all pairs \((a, a)\) for all \(a \in A\) to \(R\).

Let \(\Delta = \{(a, a) \mid a \in A\}\) be the diagonal (or identity) relation. The reflexive closure of R, denoted \(r(R)\), is: [ r(R) = R \cup \Delta ]

Example

Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(R = \{(1, 2), (2, 2), (3, 1)\}\). The diagonal relation is \(\Delta = \{(1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3)\}\). The reflexive closure is \(r(R) = R \cup \Delta = \{(1, 2), (2, 2), (3, 1), (1, 1), (3, 3)\}\).

Symmetric Closure¶

The symmetric closure of a relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is the smallest symmetric relation containing \(R\). It is obtained by adding the inverse pair \((b, a)\) for every pair \((a, b)\) in \(R\).

Let \(R^{-1} = \{(b, a) \mid (a, b) \in R\}\) be the inverse relation. The symmetric closure of R, denoted \(s(R)\), is: [ s(R) = R \cup R^{-1} ]

Example

Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(R = \{(1, 2), (2, 3)\}\). The inverse relation is \(R^{-1} = \{(2, 1), (3, 2)\}\). The symmetric closure is \(s(R) = R \cup R^{-1} = \{(1, 2), (2, 3), (2, 1), (3, 2)\}\).

Transitive Closure¶

The transitive closure of a relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is the smallest transitive relation containing \(R\). It contains the pair \((a, c)\) if there is a "path" of one or more steps from \(a\) to \(c\) in the original relation.

The transitive closure is often denoted as \(R^+\) or \(t(R)\). If \(R^n\) is the composition of \(R\) with itself \(n\) times, then the transitive closure is the union of all such compositions.

For a finite set \(A\) with \(|A| = k\), this simplifies to:

Finding Transitive Closure: Warshall's Algorithm¶

Warshall's algorithm is an efficient method to compute the transitive closure of a relation using its matrix representation.

- Start with the relation matrix, \(M_R\). Let's call it \(W\). \(W\) is an \(n \times n\) matrix.

- Iterate from \(k = 1\) to \(n\). In each iteration, update the matrix.

- The update rule is: For every pair of indices \((i, j)\), set \(W_{ij} = W_{ij} \lor (W_{ik} \land W_{kj})\).

- After iterating through all \(k\) from 1 to \(n\), the resulting matrix \(W\) will be the matrix of the transitive closure, \(M_{R^+}\).

This rule essentially says: "There is a path from vertex \(i\) to vertex \(j\) if there was already a direct edge, OR if there is a path from \(i\) to \(k\) AND a path from \(k\) to \(j\)". By iterating through all possible intermediate vertices \(k\), we find all possible paths.

Reflexive Transitive Closure¶

The reflexive transitive closure, denoted \(R^*\), is the smallest relation that is both reflexive and transitive. It represents reachability, meaning \((a, b) \in R^*\) if \(b\) is reachable from \(a\) in zero or more steps.

It is simply the union of the transitive closure and the diagonal relation.

Alternatively, it can be defined as:

where \(R^0 = \Delta\).

Relations and Partitions¶

Equivalence Relations¶

An equivalence relation is a specific type of binary relation on a set that generalizes the concept of equality. It is a relation that is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

Let \(R\) be a binary relation on a non-empty set \(A\). \(R\) is an equivalence relation if it satisfies the following three properties:

Reflexivity¶

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is reflexive if every element of \(A\) is related to itself.

- Example: The relation 'is equal to' (=) on the set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}\) is reflexive because for any integer \(a\), \(a = a\).

- Non-Example: The relation 'is greater than' (>) on \(\mathbb{Z}\) is not reflexive because \(a > a\) is never true.

Symmetry¶

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is symmetric if whenever an element \(a\) is related to an element \(b\), then \(b\) is also related to \(a\).

- Example: The relation "is a cousin of" on a set of people is symmetric. If Ram is a cousin of Sita, then Sita is a cousin of Ram.

- Non-Example: The relation 'is less than or equal to' (≤) on \(\mathbb{Z}\) is not symmetric. We know that \(3 \le 5\), but \(5 \not\le 3\).

Transitivity¶

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is transitive if whenever an element \(a\) is related to \(b\), and \(b\) is related to \(c\), then \(a\) is also related to \(c\).

- Example: The relation 'is a descendant of' is transitive. If B is a descendant of A, and C is a descendant of B, then C is also a descendant of A.

- Non-Example: The relation "is the father of" is not transitive. If A is the father of B, and B is the father of C, A is the grandfather of C, not the father.

Example of an Equivalence Relation¶

Let's consider the set of all integers, \(\mathbb{Z}\). Define a relation \(R\) such that \((a, b) \in R\) if and only if \(a \equiv b \pmod{m}\), which means \(m\) divides \((a - b)\) for some fixed integer \(m > 1\). This is called congruence modulo m.

Let's check the three properties for \(m=3\). So, \((a, b) \in R\) if \((a - b)\) is a multiple of 3.

Reflexive: For any integer \(a\), \(a - a = 0\). Since \(0 = 3 \times 0\), \(0\) is a multiple of 3. Thus, \((a, a) \in R\). The relation is reflexive.

Symmetric: Suppose \((a, b) \in R\). This means \((a - b)\) is a multiple of 3. So, \(a - b = 3k\) for some integer \(k\). Then, \(b - a = -(a - b) = -3k = 3(-k)\). Since \(-k\) is also an integer, \((b - a)\) is a multiple of 3. Thus, \((b, a) \in R\). The relation is symmetric.

Transitive: Suppose \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, c) \in R\). This means \((a - b) = 3k\) and \((b - c) = 3j\) for some integers \(k\) and \(j\). Now consider \(a - c\):

Since \(k+j\) is an integer, \((a-c)\) is a multiple of 3. Thus, \((a, c) \in R\). The relation is transitive.

Since the relation is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive, congruence modulo 3 is an equivalence relation on the set of integers.

Equivalence Classes¶

Given an equivalence relation \(R\) on a set \(A\), the equivalence class of an element \(a \in A\), denoted by \([a]\) or \(\bar{a}\), is the set of all elements in \(A\) that are related to \(a\).

Essentially, an equivalence class is a subset of \(A\) containing all elements that are "equivalent" to each other under the relation \(R\).

Example of Equivalence Classes¶

Using the congruence modulo 3 relation on \(\mathbb{Z}\) from the previous example:

-

The equivalence class of 0, denoted [0]: This is the set of all integers \(x\) such that \(x \equiv 0 \pmod{3}\). This means \(x - 0\) is a multiple of 3. These are all the multiples of 3. [ [0] = { \dots, -6, -3, 0, 3, 6, \dots } ]

-

The equivalence class of 1, denoted [1]: This is the set of all integers \(x\) such that \(x \equiv 1 \pmod{3}\). This means \(x - 1\) is a multiple of 3. [ [1] = { \dots, -5, -2, 1, 4, 7, \dots } ]

-

The equivalence class of 2, denoted [2]: This is the set of all integers \(x\) such that \(x \equiv 2 \pmod{3}\). This means \(x - 2\) is a multiple of 3. [ [2] = { \dots, -4, -1, 2, 5, 8, \dots } ]

What about \([3]\)? An integer \(x\) is in \([3]\) if \(x - 3\) is a multiple of 3. If \(x-3 = 3k\), then \(x = 3k+3 = 3(k+1)\), which means \(x\) is a multiple of 3. So, \([3] = [0]\). Similarly, \([4] = [1]\), \([-1] = [2]\), and so on.

Properties of Equivalence Classes¶

Let \(R\) be an equivalence relation on a set \(A\), and let \(a, b \in A\).

- \(a \in [a]\). (Every element belongs to its own equivalence class).

- If \((a, b) \in R\), then \([a] = [b]\).

- If \((a, b) \notin R\), then \([a] \cap [b] = \emptyset\).

- Any two equivalence classes are either identical or disjoint (they have no elements in common).

- The set of all equivalence classes forms a partition of the set \(A\).

Partitions¶

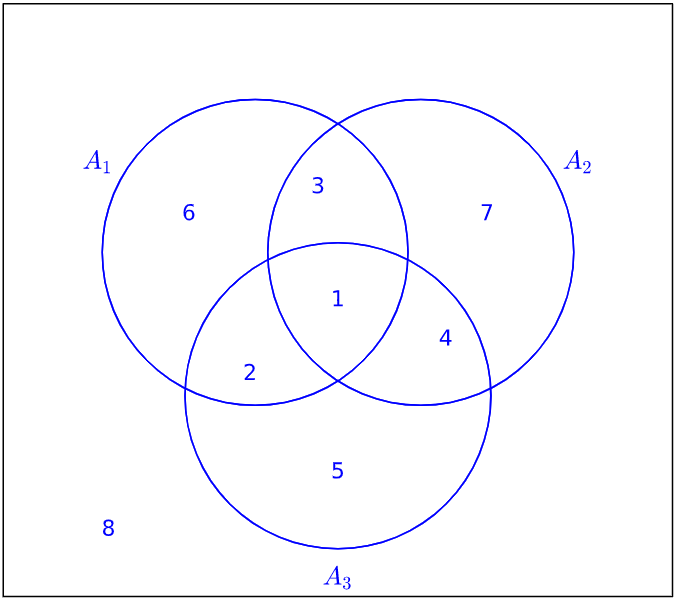

A partition of a non-empty set \(A\) is a collection of non-empty subsets of \(A\), say \(A_1, A_2, \dots, A_n\), such that these subsets are pairwise disjoint and their union is the entire set \(A\).

Formally, a collection of subsets \(\{A_i \mid i \in I\}\) (where \(I\) is an index set) is a partition of \(A\) if it satisfies three conditions:

-

Non-empty: No subset is empty.

\[ \forall i \in I, A_i \neq \emptyset \] -

Pairwise Disjoint: The intersection of any two distinct subsets is the empty set.

\[ \forall i, j \in I, \text{ if } i \neq j, \text{ then } A_i \cap A_j = \emptyset \] -

Covers the Set: The union of all the subsets is the original set \(A\).

\[ \bigcup_{i \in I} A_i = A \]

Example of a Partition¶

Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\).

-

The collection of subsets \(\{\{1, 3\}, \{2\}, \{4, 5, 6\}\}\) is a partition of \(A\) because:

- None of the subsets are empty.

- They are pairwise disjoint: \(\{1, 3\} \cap \{2\} = \emptyset\), \(\{1, 3\} \cap \{4, 5, 6\} = \emptyset\), and \(\{2\} \cap \{4, 5, 6\} = \emptyset\).

- Their union is \(A\): \(\{1, 3\} \cup \{2\} \cup \{4, 5, 6\} = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\} = A\).

-

The collection \(\{\{1, 2\}, \{2, 3\}, \{4, 5, 6\}\}\) is not a partition because the subsets \(\{1, 2\}\) and \(\{2, 3\}\) are not disjoint (\(\{1, 2\} \cap \{2, 3\} = \{2\}\)).

The Fundamental Theorem of Equivalence Relations¶

There is a fundamental connection between equivalence relations and partitions.

Theorem

- An equivalence relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) partitions the set \(A\) into its equivalence classes.

- Conversely, any partition of a set \(A\) induces an equivalence relation on \(A\).

This means equivalence relations and partitions are two different ways of looking at the same concept of grouping elements.

From Equivalence Relation to Partition¶

As we saw with the congruence modulo 3 example, the equivalence classes were:

- \([0] = \{ \dots, -6, -3, 0, 3, 6, \dots \}\)

- \([1] = \{ \dots, -5, -2, 1, 4, 7, \dots \}\)

- \([2] = \{ \dots, -4, -1, 2, 5, 8, \dots \}\)

The collection of these classes \(\{[0], [1], [2]\}\) forms a partition of the set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}\):

- Non-empty: None of the classes are empty.

- Disjoint: \([0] \cap [1] = \emptyset\), \([0] \cap [2] = \emptyset\), and \([1] \cap [2] = \emptyset\).

- Union is \(\mathbb{Z}\): Every integer belongs to one of these three classes (it either has a remainder of 0, 1, or 2 when divided by 3). So, \([0] \cup [1] \cup [2] = \mathbb{Z}\).

From Partition to Equivalence Relation¶

Let's take our example partition of \(A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\) as \(P = \{\{1, 3\}, \{2\}, \{4, 5, 6\}\}\).

We can define a relation \(R\) on \(A\) where \((a, b) \in R\) if and only if \(a\) and \(b\) are in the same subset of the partition \(P\).

- Elements related to each other:

- \((1, 1), (3, 3), (1, 3), (3, 1)\)

- \((2, 2)\)

- \((4, 4), (5, 5), (6, 6), (4, 5), (5, 4), (4, 6), (6, 4), (5, 6), (6, 5)\)

This relation \(R\) will be an equivalence relation:

- Reflexive: Every element is in the same subset as itself. E.g., \((1,1) \in R\).

- Symmetric: If \(a\) is in the same subset as \(b\), then \(b\) is in the same subset as \(a\). E.g., if \((1,3) \in R\), then \((3,1) \in R\).

- Transitive: If \(a\) and \(b\) are in the same subset, and \(b\) and \(c\) are in the same subset, then \(a\) and \(c\) must be in that same subset. E.g., \((4,5) \in R\) and \((5,6) \in R\), which implies \((4,6) \in R\). All three are in the subset \(\{4, 5, 6\}\).

N-ary Relations¶

“This topic is not important for mathematics, but for DBMS (Database Management System).”

An n-ary relation is a fundamental concept in set theory and is the theoretical foundation for relational databases. While binary relations (where n=2) connect elements from two sets, n-ary relations generalize this idea to connect elements from any number of sets.

Definition of an N-ary Relation¶

Let \(A_1, A_2, \dots, A_n\) be \(n\) sets. An n-ary relation \(R\) on these sets is any subset of the Cartesian product \(A_1 \times A_2 \times \dots \times A_n\).

Mathematically, this is expressed as: [ R \subseteq A_1 \times A_2 \times \dots \times A_n ]

- The sets \(A_1, A_2, \dots, A_n\) are called the domains of the relation.

- The number \(n\) is called the degree or arity of the relation.

The elements of an n-ary relation are ordered n-tuples of the form \((a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n)\), where \(a_1 \in A_1, a_2 \in A_2, \dots, a_n \in A_n\).

Types of Relations based on Degree¶

- Unary Relation (n=1): A subset of a single set \(A_1\). It essentially specifies a property of the elements in \(A_1\).

- Binary Relation (n=2): A subset of \(A_1 \times A_2\). This is the most commonly studied type, e.g., 'less than' (<) on the set of integers.

- Ternary Relation (n=3): A subset of \(A_1 \times A_2 \times A_3\).

- Quaternary Relation (n=4): A subset of \(A_1 \times A_2 \times A_3 \times A_4\).

- And so on for any integer \(n > 0\).

Example: A Ternary Relation¶

Consider a university database scenario. We can define a ternary relation Enrolled to capture which student is enrolled in which course and taught by which professor.

-

Let the domains be:

Students= {Anjali, Rohan, Priya}Courses= {CS101, MA202, PH110}Professors= {Dr. Gupta, Dr. Sharma, Dr. Verma}

-

The Cartesian product

Students\(\times\)Courses\(\times\)Professorswould contain all possible combinations, like (Anjali, CS101, Dr. Gupta), (Anjali, CS101, Dr. Sharma), etc. -

The

Enrolledrelation is a subset of this Cartesian product that represents the actual enrollments. For example:\[ \begin{align*} \text{Enrolled} = \{ & (\text{Anjali, CS101, Dr. Gupta}), \\ & (\text{Rohan, CS101, Dr. Gupta}), \\ & (\text{Rohan, MA202, Dr. Sharma}), \\ & (\text{Priya, PH110, Dr. Verma}) \} \end{align*} \]

This relation tells us that Anjali is enrolled in CS101 taught by Dr. Gupta, Rohan is in CS101 with Dr. Gupta and MA202 with Dr. Sharma, and so on. The tuple (Anjali, MA202, Dr. Gupta) is not in the relation, which means Anjali is not enrolled in MA202 with Dr. Gupta.

Representation of N-ary Relations as Tables¶

The most intuitive and practical way to represent an n-ary relation is using a table. This is the core principle behind the relational model for databases.

Correspondence between Relation and Table¶

| Mathematical Concept | Database Table Component |

|---|---|

N-ary Relation Name (e.g., Enrolled) |

Table Name |

| Degree of the Relation (\(n\)) | Number of Columns |

| Domain (\(A_i\)) | Attribute / Column |

| Attribute Name | Column Header |

| n-tuple (\((a_1, \dots, a_n) \in R\)) | Row / Record / Tuple |

Example: Representing the Enrolled Relation¶

The ternary relation Enrolled from the previous example can be represented as the following table:

Table: Enrolled

| Student_Name | Course_ID | Professor_Name |

|---|---|---|

| Anjali | CS101 | Dr. Gupta |

| Rohan | CS101 | Dr. Gupta |

| Rohan | MA202 | Dr. Sharma |

| Priya | PH110 | Dr. Verma |

Key Observations:¶

-

Columns represent Domains: Each column in the table corresponds to one of the sets (domains) in the Cartesian product. The column header (e.g.,

Student_Name) is the attribute that draws its values from the corresponding domain (e.g.,Students). -

Rows represent Tuples: Each row in the table is an n-tuple that belongs to the relation. The row

(Anjali, CS101, Dr. Gupta)signifies that this 3-tuple is an element of theEnrolledrelation. -

Order of Rows is Immaterial: Since a relation is a set of tuples, the order of these tuples is not important. Similarly, the order of rows in a database table is considered insignificant. The table with Rohan's entries listed first would represent the exact same relation.

-

Order of Columns is Formally Significant: In the formal definition of a tuple, the order of elements matters. \((a_1, a_2)\) is different from \((a_2, a_1)\). However, in the practical table representation, columns are identified by their names (attributes). So, while we can reorder the columns visually, the association between a column's name and its data is fixed.

-

No Duplicate Rows: By the definition of a set, it cannot contain duplicate elements. This translates directly to the table representation: a table representing a relation cannot have two identical rows. In database systems, this is often enforced by a primary key, which is a unique identifier for each row.

Another Example: A 4-ary (Quaternary) Relation¶

Let's define a relation FLIGHTS with degree 4.

-

Domains:

FlightNum: {AI202, 6E155, UK810}Origin: {Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru}Destination: {Kolkata, Chennai, Delhi}DepartureTime: {08:00, 14:30, 21:00}

-

Relation (as a set of 4-tuples):

\[ \begin{align*} \text{FLIGHTS} = \{ & (\text{AI202, Delhi, Kolkata, 08:00}), \\ & (\text{6E155, Mumbai, Chennai, 14:30}), \\ & (\text{UK810, Bengaluru, Delhi, 21:00}), \\ & (\text{AI202, Kolkata, Delhi, 14:30}) \} \end{align*} \] -

Representation as a Table:

Table: FLIGHTS

| Flight_Number | Source_City | Destination_City | Dep_Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI202 | Delhi | Kolkata | 08:00 |

| 6E155 | Mumbai | Chennai | 14:30 |

| UK810 | Bengaluru | Delhi | 21:00 |

| AI202 | Kolkata | Delhi | 14:30 |

This tabular representation is clear, organized, and provides a structured way to view and query the relationships between data elements, forming the basis of modern database management systems.

Partial Ordering Relations and Lattices¶

Relations¶

A binary relation \(R\) from a set \(A\) to a set \(B\) is a subset of the Cartesian product \(A \times B\). If \(A = B\), we say that \(R\) is a relation on the set \(A\). If \((a, b) \in R\), we can also write \(aRb\), which means "\(a\) is related to \(b\)".

Partial Ordering Relations¶

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is called a partial ordering relation (or partial order) if it is:

- Reflexive: For all \(a \in A\), \((a, a) \in R\).

- Every element is related to itself.

- Antisymmetric: For all \(a, b \in A\), if \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, a) \in R\), then \(a = b\).

- If two distinct elements are related, the relation cannot go in both directions.

- Transitive: For all \(a, b, c \in A\), if \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, c) \in R\), then \((a, c) \in R\).

- If \(a\) is related to \(b\) and \(b\) is related to \(c\), then \(a\) must be related to \(c\).

A set \(A\) together with a partial ordering relation \(R\) is called a Partially Ordered Set or Poset, denoted as \((A, R)\). It is common to use symbols like \(\leq\) or \(\preceq\) to represent a generic partial order relation.

Examples of Posets

- The set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}\) with the "less than or equal to" relation \((\mathbb{Z}, \leq)\) is a poset.

- Reflexive: \(a \leq a\) for any integer \(a\).

- Antisymmetric: If \(a \leq b\) and \(b \leq a\), then \(a = b\).

- Transitive: If \(a \leq b\) and \(b \leq c\), then \(a \leq c\).

- The power set of a set \(A\), \(\mathcal{P}(A)\), with the subset relation \((\mathcal{P}(A), \subseteq)\) is a poset.

- Reflexive: \(X \subseteq X\) for any set \(X \in \mathcal{P}(A)\).

- Antisymmetric: If \(X \subseteq Y\) and \(Y \subseteq X\), then \(X = Y\).

- Transitive: If \(X \subseteq Y\) and \(Y \subseteq Z\), then \(X \subseteq Z\).

- The set of positive integers \(\mathbb{Z}^+\) with the "divides" relation \((\mathbb{Z}^+, |)\) is a poset.

- Reflexive: \(a | a\) for any \(a \in \mathbb{Z}^+\).

- Antisymmetric: If \(a | b\) and \(b | a\), then \(a = b\).

- Transitive: If \(a | b\) and \(b | c\), then \(a | c\).

Hasse Diagrams¶

A Hasse diagram is a graphical representation of a finite poset. It simplifies the directed graph of the relation by:

- Removing all self-loops that result from the reflexive property.

- Removing all transitive edges. We only show the "immediate" relationships.

- Arranging the vertices such that all edges point upwards, allowing us to omit the arrowheads.

To construct a Hasse diagram:

- Start with the directed graph of the relation on the set.

- Remove all edges of the form \((a, a)\).

- Remove all edges \((a, c)\) for which there already exist edges \((a, b)\) and \((b, c)\).

- Draw the resulting graph with vertices arranged so that if \(a \preceq b\), then \(b\) is placed above \(a\).

- Remove the arrowheads from the edges.

Elements in a Poset¶

Let \((S, \preceq)\) be a poset and \(A \subseteq S\).

- Maximal Element: An element \(a \in S\) is maximal if there is no other element \(b \in S\) such that \(a \preceq b\) and \(a \neq b\).

- Minimal Element: An element \(a \in S\) is minimal if there is no other element \(b \in S\) such that \(b \preceq a\) and \(a \neq b\).

- Greatest Element (Top): An element \(a \in S\) is the greatest element if \(b \preceq a\) for all \(b \in S\). It is unique if it exists. Denoted by \(1\) or \(\top\).

- Least Element (Bottom): An element \(a \in S\) is the least element if \(a \preceq b\) for all \(b \in S\). It is unique if it exists. Denoted by \(0\) or \(\bot\).

- Upper Bound: An element \(u \in S\) is an upper bound of \(A\) if \(a \preceq u\) for all \(a \in A\).

- Lower Bound: An element \(l \in S\) is a lower bound of \(A\) if \(l \preceq a\) for all \(a \in A\).

- Least Upper Bound (LUB or Supremum): An upper bound \(u\) of \(A\) is the least upper bound if \(u \preceq v\) for any other upper bound \(v\) of \(A\). Denoted as \(sup(A)\).

- Greatest Lower Bound (GLB or Infimum): A lower bound \(l\) of \(A\) is the greatest lower bound if \(m \preceq l\) for any other lower bound \(m\) of \(A\). Denoted as \(inf(A)\).

Lattices¶

A lattice is a poset \((L, \preceq)\) in which every pair of elements \(\{a, b\}\) has a unique least upper bound (LUB) and a unique greatest lower bound (GLB).

- The LUB of \(\{a, b\}\) is called the join of \(a\) and \(b\), denoted by \(a \vee b\).

- The GLB of \(\{a, b\}\) is called the meet of \(a\) and \(b\), denoted by \(a \wedge b\).

So, a poset is a lattice if \(a \vee b\) and \(a \wedge b\) exist for all \(a, b \in L\).

Examples of Lattices

- \((\mathbb{Z}, \leq)\) is a lattice. For any integers \(a, b\), \(a \vee b = \max(a, b)\) and \(a \wedge b = \min(a, b)\).

- \((\mathcal{P}(A), \subseteq)\) is a lattice. For any subsets \(X, Y \subseteq A\), \(X \vee Y = X \cup Y\) and \(X \wedge Y = X \cap Y\).

- \((\mathbb{Z}^+, |)\) is a lattice. For any positive integers \(a, b\), \(a \vee b = \text{lcm}(a, b)\) and \(a \wedge b = \text{gcd}(a, b)\).

Properties of Lattices¶

For any elements \(a, b, c\) in a lattice \(L\):

- Idempotent Laws:

- \(a \vee a = a\)

- \(a \wedge a = a\)

- Commutative Laws:

- \(a \vee b = b \vee a\)

- \(a \wedge b = b \wedge a\)

- Associative Laws:

- \((a \vee b) \vee c = a \vee (b \vee c)\)

- \((a \wedge b) \wedge c = a \wedge (b \wedge c)\)

- Absorption Laws:

- \(a \vee (a \wedge b) = a\)

- \(a \wedge (a \vee b) = a\)

Special Types of Lattices¶

Bounded Lattice¶

A lattice \(L\) is bounded if it has a greatest element \(1\) (top) and a least element \(0\) (bottom). - \(a \vee 1 = 1\) and \(a \wedge 1 = a\) - \(a \vee 0 = a\) and \(a \wedge 0 = 0\)

Distributive Lattice¶

A lattice \(L\) is distributive if the distributive laws hold for all \(a, b, c \in L\): 1. \(a \wedge (b \vee c) = (a \wedge b) \vee (a \wedge c)\) (Meet distributes over Join) 2. \(a \vee (b \wedge c) = (a \vee b) \wedge (a \vee c)\) (Join distributes over Meet)

Note

In any lattice, one of these properties implies the other. A lattice is non-distributive if it contains a sublattice isomorphic to the "diamond lattice" \(M_3\) or the "pentagon lattice" \(N_5\).

Complemented Lattice¶

A complemented lattice is a bounded lattice \((L, \preceq, \vee, \wedge, 0, 1)\) in which every element \(a \in L\) has a complement, denoted as \(a'\) or \(\bar{a}\), such that: - \(a \vee a' = 1\) - \(a \wedge a' = 0\)

The complement of an element may not be unique.

Boolean Lattice (Boolean Algebra)¶

A lattice is a Boolean lattice or Boolean algebra if it is both distributive and complemented. In a Boolean algebra, the complement of every element is unique.

Summary

- Poset: Reflexive, Antisymmetric, Transitive.

- Lattice: A poset where every pair has a unique LUB (join \(\vee\)) and GLB (meet \(\wedge\)).

- Bounded Lattice: A lattice with a greatest (1) and a least (0) element.

- Distributive Lattice: A lattice where meet distributes over join (and vice versa).

- Complemented Lattice: A bounded lattice where every element has a complement.

- Boolean Algebra: A lattice that is both distributive and complemented.

Problem Set¶

Definition and Properties of Binary Relations¶

-

Let \( A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\} \). A relation \( R \) is defined on \( A \) as \( R = \{(a, b) \mid a \text{ divides } b\} \).

- Write down all the ordered pairs in \( R \).

- Represent \( R \) as a matrix.

- Draw the directed graph (digraph) for \( R \).

-

For each of the following relations on the set of integers \( \mathbb{Z} \), determine whether it is reflexive, symmetric, antisymmetric, and/or transitive. Justify your answers.

- \( R_1 = \{(a, b) \mid a \leq b\} \)

- \( R_2 = \{(a, b) \mid a = b \text{ or } a = -b\} \)

- \( R_3 = \{(a, b) \mid a = b+1\} \)

- \( R_4 = \{(a, b) \mid a + b \text{ is an even number}\} \)

- \( R_5 = \{(a, b) \mid ab \geq 0\} \)

-

Let \( S = \{a, b, c\} \). Give an example of a relation on \( S \) that is:

- Symmetric but not transitive.

- Transitive but not symmetric.

- Antisymmetric and transitive but not reflexive.

- Reflexive and symmetric but not transitive.

-

Consider the relation \( R \) on the set of all people, where \( (a, b) \in R \) if person \( a \) is a sibling of person \( b \). Is this relation reflexive, symmetric, antisymmetric, or transitive? (Assume a person cannot be their own sibling).

-

Let \( A \) be the set of all strings of English letters. Define a relation \( R \) on \( A \) by \( s_1 R s_2 \) if length(\( s_1 \)) = length(\( s_2 \)). Prove that \( R \) is an equivalence relation.

-

Let \( R \) be the relation on the set of real numbers \( \mathbb{R} \) defined by \( x R y \) if \( x - y \) is a rational number. Determine the properties (reflexive, symmetric, transitive) of \( R \).

-

If \( R_1 \) and \( R_2 \) are two transitive relations on a set \( A \), is \( R_1 \cup R_2 \) necessarily transitive? Prove or provide a counterexample.

-

Let \( R \) be the relation "congruence modulo 5" on the set of integers \( \mathbb{Z} \). That is, \( x R y \) if \( x \equiv y \pmod{5} \). Show that \( R \) has all the properties of an equivalence relation.

-

Represent the relation \( R = \{(1,1), (1,4), (2,2), (2,5), (3,3), (4,1), (4,4), (5,2), (5,5)\} \) on the set \( A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} \) using a zero-one matrix.

-

Draw the digraph for the relation from the previous question. From the digraph, determine if the relation is reflexive, symmetric, or antisymmetric.

-

Let \( P \) be the set of all programs. Define a relation \( R \) on \( P \) such that \( (p_1, p_2) \in R \) if program \( p_1 \) contains more lines of code than program \( p_2 \). What properties does this relation have?

-

Prove that if a relation \( R \) on a set \( A \) is symmetric, then its inverse \( R^{-1} \) is also symmetric.

Closures of Relations¶

-

Let \( A = \{a, b, c\} \) and \( R = \{(a, b), (b, c), (c, a)\} \). Find the reflexive closure of \( R \).

-

Let \( A = \{1, 2, 3\} \) and \( R = \{(1, 2), (2, 1), (2, 3)\} \). Find the symmetric closure of \( R \).

-

Find the reflexive and symmetric closures of the relation \( R = \{(x, y) \mid x, y \in \mathbb{Z}, x < y\} \).

-

Let \( R \) be a relation on a set \( A \). Prove that the reflexive closure of \( R \) is \( R \cup \Delta_A \), where \( \Delta_A = \{(a, a) \mid a \in A\} \).

-

Let \( M_R \) be the matrix representation of a relation \( R \) on a set with \( n \) elements. How can you find the matrix representation for the reflexive closure of \( R \)?

-

Let \( R = \{(1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4)\} \) on the set \( A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\} \). Find the transitive closure \( R^* \) of \( R \).

-

Use Warshall's Algorithm to find the transitive closure of the relation represented by the following matrix on the set \( \{a, b, c, d\} \): [ M_R = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} ]

-

Let \( R \) be the relation on \( \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} \) defined by \( R = \{(1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (4, 5)\} \). Find the reflexive transitive closure of \( R \).

-

What is the transitive closure of the relation \( R = \{(a, b) \mid a \text{ is a parent of } b\} \) on the set of all people?

-

Let \( R \) be a relation on \( A \). Prove that the transitive closure of \( R \), \( R^* \), is the smallest transitive relation containing \( R \).

Equivalence Relations and Partitions¶

-

Which of the relations in question 2 are equivalence relations? For those that are, describe their equivalence classes.

-

Let \( A \) be the set of all students at a university. Define \( (a, b) \in R \) if student \( a \) and student \( b \) are enrolled in the same course. Is \( R \) an equivalence relation? Explain.

-

Let \( R \) be the relation on the set of ordered pairs of positive integers such that \( ((a, b), (c, d)) \in R \) if and only if \( ad = bc \). Show that \( R \) is an equivalence relation.

-

What are the equivalence classes of the relation from the previous question? (Hint: Think about what \( \frac{a}{b} = \frac{c}{d} \) means).

-

Find the partition of the set \( A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7\} \) corresponding to the equivalence relation \( R = \{(a, b) \mid a \equiv b \pmod{3}\} \).

-

Let \( \mathcal{P} = \{\{1, 5\}, \{2, 4, 6\}, \{3\}\} \) be a partition of the set \( S = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\} \). Write down the equivalence relation \( R \) that induces this partition.

-

State the Fundamental Theorem of Equivalence Relations. Explain its significance in your own words.

-

Let \( f: A \to B \) be a function. Define a relation \( R \) on \( A \) by \( x R y \) if \( f(x) = f(y) \).

- Prove that \( R \) is an equivalence relation on \( A \).

- Describe the equivalence classes of \( R \).

-

Can \( \{\{1, 2\}, \{2, 3\}, \{4\}\} \) be a partition of \( \{1, 2, 3, 4\} \)? Why or why not?

-

Let \( A \) be the set of all bit strings of length 8. Define a relation \( R \) on \( A \) where \( s_1 R s_2 \) if \( s_1 \) and \( s_2 \) have the same number of 1s.

- Show \( R \) is an equivalence relation.

- How many distinct equivalence classes are there?

-

How many different equivalence relations can be defined on a set with 3 elements? Describe the corresponding partitions.

-

A relation \( R \) is called a circular relation if \( (a,b) \in R \) and \( (b,c) \in R \) implies \( (c,a) \in R \). Prove that a relation is an equivalence relation if and only if it is reflexive and circular.

-

Let \( R \) be the relation on the set of points in the Cartesian plane \( \mathbb{R}^2 \) where \( (x_1, y_1) R (x_2, y_2) \) if \( x_1^2 + y_1^2 = x_2^2 + y_2^2 \). Describe the equivalence classes geometrically.

N-ary Relations¶

-

Define a 4-ary relation on the set of integers that would represent the equation \( a + b = c + d \).

-

Consider the following table representing a ternary relation

STUDENT_COURSE_GRADEon the setsStudents,Courses,Grades.

| Student_ID | Course_ID | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | CS101 | A |

| 102 | CS101 | B |

| 101 | MA203 | B |

| 103 | PHY101 | C |

| 102 | MA203 | A |

- What is the degree of this relation?

-

Write down all the 3-tuples that are part of this relation.

-

From the table in the previous question, what is the result of selecting all tuples where

Course_ID = 'CS101'? -

Explain the correspondence between an n-ary relation and a table in a relational database. What do the columns and rows represent?

-

Create a 5-ary relation representing a

Flightentity with attributes:FlightNumber,Origin,Destination,DepartureTime,ArrivalTime. Provide 3 example tuples for this relation.

Partial Ordering Relations and Lattices¶

-

Define a partial ordering relation. Why is it called "partial"?

-

Let \( S = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12\} \). The relation is "divisibility". Show that this relation is a partial ordering on \( S \).

-

Draw the Hasse diagram for the poset described in the previous question.

-

Consider the power set of \( \{a, b, c\} \), denoted \( \mathcal{P}(\{a, b, c\}) \), with the subset relation \( \subseteq \).

- Draw the Hasse diagram for this poset.

- Is this poset a total order? Explain.

-

For the poset \( (\mathcal{P}(\{a, b, c\}), \subseteq) \), find:

- The maximal elements.

- The minimal elements.

- The greatest element.

- The least element.

-

For the poset represented by the Hasse diagram from question 43, find:

- All upper bounds of the set \( \{2, 3\} \).

- The least upper bound (lub) of \( \{2, 3\} \).

- All lower bounds of the set \( \{6, 12\} \).

- The greatest lower bound (glb) of \( \{6, 12\} \).

-

A relation \( R \) on a set \( A \) is a total order (or linear order) if it is a partial order and for every \( a, b \in A \), either \( (a, b) \in R \) or \( (b, a) \in R \). Give an example of a poset that is not a total order.

-

Define a lattice. Is the poset from question 44 a lattice? Justify your answer by checking if every pair of elements has a lub and a glb.

-

Consider the set of positive integers \( \mathbb{Z}^+ \) with the divisibility relation. Is this a lattice? If so, what are the meet (\(\wedge\)) and join (\(\vee\)) operations for any two integers \( a \) and \( b \)?

-

Draw the Hasse diagram for the poset \( (\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}, \leq) \) where \( \leq \) is the standard "less than or equal to" relation. Is this a lattice?

Special Lattices and Boolean Algebra¶

-

What is a bounded lattice? Give an example. Is the lattice from question 44 bounded? If so, what are its bounds (0 and 1)?

-

Define a distributive lattice. Show that the lattice \( (\mathcal{P}(\{a, b\}), \subseteq) \) is distributive.

-

Consider the "diamond" lattice, with elements \( \{0, a, b, c, 1\} \) where \( 0 < a, b, c < 1 \) and \( a, b, c \) are incomparable. Draw its Hasse diagram. Is this lattice distributive? (This is the standard \( M_3 \) lattice).

-

Define a complemented lattice. Show that \( (\mathcal{P}(\{a, b, c\}), \subseteq) \) is a complemented lattice. What is the complement of the element \( \{a, b\} \)?

-

Is the lattice of divisors of 12 (from question 43) a complemented lattice? Find the complement for each element if it exists.

-

Define Boolean Algebra (or Boolean Lattice). List its key properties.

-

Show that for any set \( S \), the power set lattice \( (\mathcal{P}(S), \subseteq) \) is a Boolean Algebra. What do the operations \( \vee \), \( \wedge \), and complement correspond to in terms of set operations?

-

In a Boolean algebra, prove the absorption law: \( a \vee (a \wedge b) = a \).

-

Simplify the Boolean expression \( (x \vee y) \wedge (x' \vee y) \) using the properties of a Boolean Algebra.

-

Consider the lattice of divisors of 30, \( D_{30} = \{1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, 30\} \) with the divisibility relation.

- Draw its Hasse diagram.

- Show that this is a Boolean Algebra.

- Find the complement of the element 6.