Functions¶

Definition of a Function¶

In mathematics, a function is a rule that establishes a relationship between two non-empty sets. It maps each element from the first set, called the domain, to exactly one element in the second set, called the codomain.

Think of a function as a machine: you put an input in (from the domain), and it gives you a specific, single output (from the codomain).

Formal Definition¶

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two non-empty sets. A function \(f\) from \(A\) to \(B\), denoted as \(f: A \to B\), is a rule or a correspondence that assigns to each element \(x\) in set \(A\) a unique element \(y\) in set \(B\).

- The element \(y\) is called the image of \(x\) under \(f\). We write this as \(y = f(x)\).

- The element \(x\) is called the pre-image of \(y\).

Key Components of a Function¶

- Domain: The set of all possible input values. For a function \(f: A \to B\), the domain is the set \(A\).

- Codomain: The set of all possible output values. For a function \(f: A \to B\), the codomain is the set \(B\).

-

Range: The set of all actual output values produced by the function. The range is always a subset of the codomain.

\[ \text{Range}(f) = \{y \in B \mid y = f(x) \text{ for some } x \in A\} \]

Essential Properties of a Function¶

For a relation to be a function, it must satisfy two crucial conditions:

- Totality: Every element in the domain \(A\) must have an image in the codomain \(B\). No element in the domain can be left unmapped.

- Uniqueness: Each element in the domain \(A\) must be mapped to exactly one element in the codomain \(B\). An input cannot have multiple outputs.

Example

Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{a, b, c, d\}\).

- Let \(f = \{(1, a), (2, b), (3, c)\}\). This is a valid function. Every element of \(A\) is mapped to a unique element in \(B\).

- Domain: \(\{1, 2, 3\}\)

- Codomain: \(\{a, b, c, d\}\)

- Range: \(\{a, b, c\}\)

- Let \(g = \{(1, a), (2, b)\}\). This is not a function because the element \(3 \in A\) is not mapped to any element in \(B\) (violates totality).

- Let \(h = \{(1, a), (1, b), (2, c), (3, d)\}\). This is not a function because the element \(1 \in A\) is mapped to two different elements, \(a\) and \(b\), in \(B\) (violates uniqueness).

One-to-One Function (Injection)¶

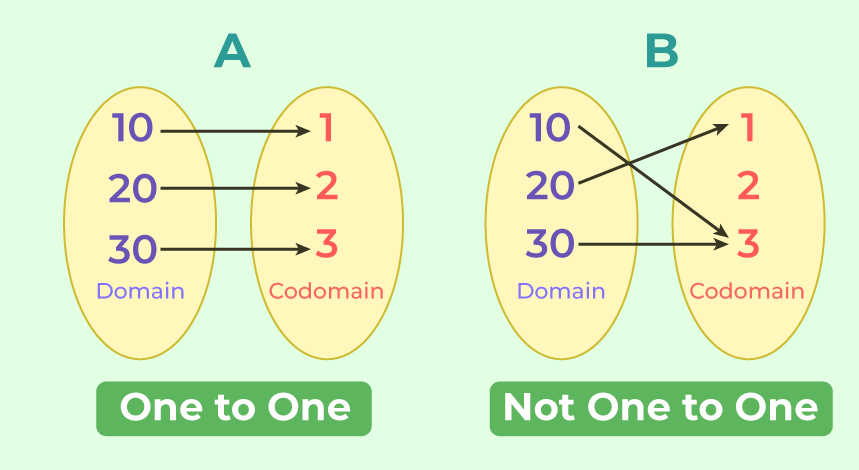

A function is one-to-one if every distinct element in the domain is mapped to a distinct element in the codomain. In other words, no two different inputs produce the same output. Such a function is also called an injective function or an injection.

Formal Definition¶

A function \(f: A \to B\) is one-to-one (injective) if for any two elements \(x_1, x_2 \in A\):

An equivalent way to state this (the contrapositive) is:

Conditions and Properties¶

- For finite sets, if a function \(f: A \to B\) is injective, then the cardinality of the domain must be less than or equal to the cardinality of the codomain: \(|A| \le |B|\).

- Graphical Test (Horizontal Line Test): A function is one-to-one if and only if no horizontal line intersects its graph at more than one point.

Example of a One-to-One Function

Let \(f: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}\) be defined by \(f(x) = x + 5\). To prove it's one-to-one, we assume \(f(x_1) = f(x_2)\) for some \(x_1, x_2 \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Subtracting 5 from both sides gives:

Since \(f(x_1) = f(x_2)\) implies \(x_1 = x_2\), the function \(f\) is one-to-one.

Example of a Function that is NOT One-to-One

Let \(g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by \(g(x) = x^2\). This function is not one-to-one. To show this, we can find a counterexample.

Let \(x_1 = 2\) and \(x_2 = -2\). Here, \(x_1 \neq x_2\). But their images are:

Since \(g(2) = g(-2)\) but \(2 \neq -2\), the function is not one-to-one.

Onto Function (Surjection)¶

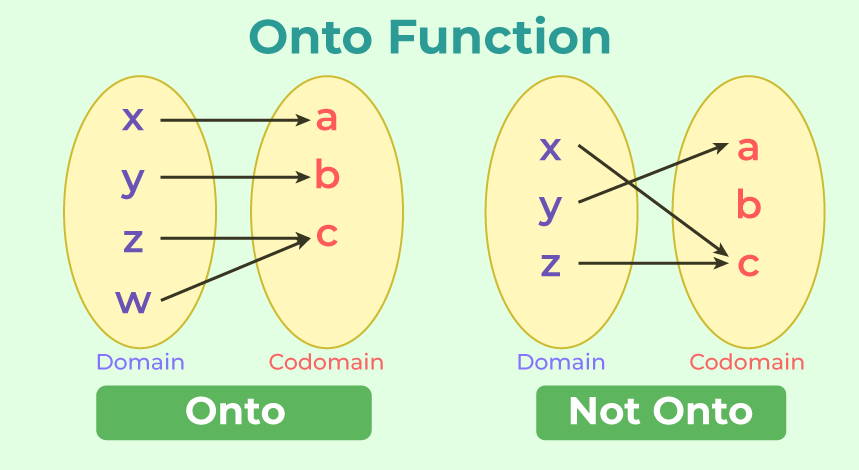

A function is onto if every element in the codomain is the image of at least one element from the domain. This means the function "hits" or "covers" every possible output value in the codomain. Such a function is also called a surjective function or a surjection.

For an onto function, the range is equal to the codomain.

Formal Definition¶

A function \(f: A \to B\) is onto (surjective) if for every element \(y \in B\), there exists at least one element \(x \in A\) such that \(f(x) = y\).

Conditions and Properties¶

- For finite sets, if a function \(f: A \to B\) is surjective, then the cardinality of the domain must be greater than or equal to the cardinality of the codomain: \(|A| \ge |B|\).

- To prove a function is onto, you must show that for any arbitrary element \(y\) in the codomain, you can find an \(x\) in the domain that maps to it.

Example of an Onto Function

Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by \(f(x) = x + 5\). To prove it's onto, we take an arbitrary element \(y\) from the codomain \(\mathbb{R}\). We need to find an \(x\) from the domain \(\mathbb{R}\) such that \(f(x) = y\).

Solving for \(x\), we get:

Since \(y\) is a real number, \(y-5\) is also a real number. This means that for any \(y \in \mathbb{R}\) we choose, we can find a corresponding \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) (which is \(y-5\)) that maps to it. Therefore, the function \(f\) is onto.

Example of a Function that is NOT Onto

Let \(g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by \(g(x) = x^2\). The codomain is the set of all real numbers, \(\mathbb{R}\). The range of \(g(x) = x^2\) is the set of all non-negative real numbers, \([0, \infty)\), because the square of any real number cannot be negative. Since the Range \([0, \infty)\) is not equal to the Codomain \(\mathbb{R}\), the function is not onto. For example, there is no real number \(x\) such that \(x^2 = -4\).

Bijective Function (One-to-One Correspondence)¶

A function is bijective if it is both one-to-one (injective) and onto (surjective). A bijective function creates a perfect pairing between the elements of the domain and the codomain.

Conditions and Properties¶

- For a function to be bijective, every element in the domain must map to a unique element in the codomain, and every element in the codomain must be mapped to by some element in the domain.

- For finite sets, if a function \(f: A \to B\) is bijective, the cardinality of the domain must be equal to the cardinality of the codomain: \(|A| = |B|\).

- Bijective functions have an inverse function, denoted \(f^{-1}\).

Example of a Bijective Function

Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by \(f(x) = 2x - 3\).

-

Is it One-to-One? Assume \(f(x_1) = f(x_2)\).

- \( 2x_1 - 3 = 2x_2 - 3 \)

- \( 2x_1 = 2x_2 \)

- \( x_1 = x_2 \)

Yes, it is one-to-one.

-

Is it Onto? Let \(y\) be an arbitrary element in the codomain \(\mathbb{R}\).

\( y = 2x - 3 \)

Solve for \(x\):

- \( y + 3 = 2x \)

- \( x = \frac{y+3}{2} \)

For any real number \(y\), \(x = (y+3)/2\) is also a real number. Thus, for any \(y\), we can find an \(x\). Yes, it is onto.

Since the function is both one-to-one and onto, it is bijective.

Principles of Mathematical Induction¶

Mathematical Induction is a powerful and fundamental proof technique in mathematics used to establish the truth of a statement for all natural numbers (or any well-ordered set starting from a specific integer). It's a formal method for proving that a property \(P(n)\) holds for every natural number \(n \ge n_0\), where \(n_0\) is some starting integer (usually 0 or 1).

The core idea is analogous to the domino effect. If you have a line of dominos: 1. You can knock over the first domino. (Base Case) 2. Each domino is placed so that if it falls, it will knock over the next one. (Inductive Step)

If both conditions are met, you can conclude that all the dominos will eventually fall.

The First Principle of Mathematical Induction (Weak Induction)¶

This is the most common form of induction. To prove a statement \(P(n)\) for all integers \(n \ge n_0\), you must complete two steps:

The Two Steps of Induction

-

Base Case (or Basis Step): Prove that the statement is true for the initial value, \(n = n_0\). This is the starting point of the proof, analogous to tipping the first domino.

-

Inductive Step: Prove that if the statement is true for an arbitrary integer \(k \ge n_0\), then it must also be true for the next integer, \(k+1\). This step consists of two parts:

- Inductive Hypothesis: Assume that \(P(k)\) is true for some arbitrary integer \(k \ge n_0\).

- Inductive Proof: Use the inductive hypothesis to show that \(P(k+1)\) is true.

If both the Base Case and the Inductive Step are proven to be true, then by the Principle of Mathematical Induction, the statement \(P(n)\) is true for all integers \(n \ge n_0\).

Example: Sum of the First \(n\) Positive Integers¶

Proposition \(P(n)\): For all integers \(n \ge 1\), the sum of the first \(n\) positive integers is given by the formula:

Proof:

-

Base Case (\(n=1\)): We need to show that \(P(1)\) is true.

- LHS (Left-Hand Side): The sum of the first 1 integer is just \(1\).

- RHS (Right-Hand Side): \(\frac{1(1+1)}{2} = \frac{1(2)}{2} = 1\). Since LHS = RHS (\(1=1\)), the base case holds. The first domino has fallen.

-

Inductive Step:

-

Inductive Hypothesis: Assume that \(P(k)\) is true for some arbitrary integer \(k \ge 1\). This means we assume:

\[ 1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + k = \frac{k(k+1)}{2} \] -

Inductive Proof: We need to prove that \(P(k+1)\) is true. That is, we need to show:

\[ 1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + k + (k+1) = \frac{(k+1)((k+1)+1)}{2} = \frac{(k+1)(k+2)}{2} \]Let's start with the LHS of \(P(k+1)\) and use our Inductive Hypothesis.

\[ \underbrace{1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + k}_{\text{This is the LHS of } P(k)} + (k+1) \]By the Inductive Hypothesis, we can substitute the sum with our formula:

\[ = \left( \frac{k(k+1)}{2} \right) + (k+1) \]Now, we use algebra to simplify the expression and show it equals the RHS of \(P(k+1)\).

\[ = \frac{k(k+1)}{2} + \frac{2(k+1)}{2} \]\[ = \frac{k(k+1) + 2(k+1)}{2} \]Factor out the common term \((k+1)\):

\[ = \frac{(k+1)(k+2)}{2} \]This is exactly the RHS of the statement for \(P(k+1)\). Thus, we have shown that if \(P(k)\) is true, then \(P(k+1)\) must also be true.

-

Conclusion: Since both the base case and the inductive step have been proven, by the principle of mathematical induction, the formula is true for all integers \(n \ge 1\).

The Second Principle of Mathematical Induction (Strong Induction)¶

Strong induction is a variant of mathematical induction where the inductive step uses a stronger assumption. Instead of just assuming \(P(k)\) is true, we assume that \(P(j)\) is true for all values from the base case up to \(k\).

The Two Steps of Strong Induction

-

Base Case (or Basis Step): Prove that the statement is true for the initial value, \(P(n_0)\). Sometimes, it is necessary to prove the statement for several initial values.

-

Inductive Step: Prove that if the statement is true for all integers \(j\) from \(n_0\) up to \(k\) (i.e., \(P(n_0), P(n_0+1), \dots, P(k)\) are all true), then it must also be true for \(k+1\).

- Inductive Hypothesis: Assume that \(P(j)\) is true for all integers \(j\) such that \(n_0 \le j \le k\).

- Inductive Proof: Use this (stronger) hypothesis to show that \(P(k+1)\) is true.

Strong induction is particularly useful in proofs where the truth of the \((k+1)\)-th case depends not just on the immediately preceding case (\(k\)) but on one or more earlier cases.

Example: Prime Factorization¶

Proposition \(P(n)\): Every integer \(n \ge 2\) can be written as a product of prime numbers.

Proof:

-

Base Case (\(n=2\)): The integer 2 is a prime number. It can be written as a product of one prime: itself. So, \(P(2)\) is true.

-

Inductive Step:

- Inductive Hypothesis (Strong): Assume that for some arbitrary integer \(k \ge 2\), the statement \(P(j)\) is true for all integers \(j\) where \(2 \le j \le k\). This means we assume every integer from 2 to \(k\) can be written as a product of primes.

-

Inductive Proof: We need to prove that \(P(k+1)\) is true. That is, we need to show that the integer \(k+1\) can be written as a product of primes. We consider two cases for \(k+1\):

-

Case 1: \(k+1\) is a prime number. If \(k+1\) is prime, then it is a product of one prime (itself). Thus, \(P(k+1)\) is true.

-

Case 2: \(k+1\) is a composite number. If \(k+1\) is composite, then by definition, it can be written as a product of two smaller integers, \(a\) and \(b\).

\[ k+1 = a \cdot b \]where \(2 \le a \le k\) and \(2 \le b \le k\).

Since both \(a\) and \(b\) are in the range \([2, k]\), our strong inductive hypothesis applies to both of them. - By the hypothesis, \(a\) can be written as a product of primes (e.g., \(p_1 \cdot p_2 \cdot \dots \)). - By the hypothesis, \(b\) can be written as a product of primes (e.g., \(q_1 \cdot q_2 \cdot \dots \)).

Therefore, \(k+1\) can be written as the product of these two sets of primes:

\[ k+1 = a \cdot b = (p_1 \cdot p_2 \cdot \dots) \cdot (q_1 \cdot q_2 \cdot \dots) \]This shows that \(k+1\) is a product of primes.

-

In both possible cases, \(P(k+1)\) is true.

Conclusion: Since the base case and the inductive step hold, by the principle of strong mathematical induction, every integer \(n \ge 2\) can be written as a product of prime numbers.

Convex and Concave Functions¶

Functions can be classified based on their curvature. This classification is crucial in fields like optimization, calculus, and economics. The primary types of curvature are convex and concave.

Convex Functions¶

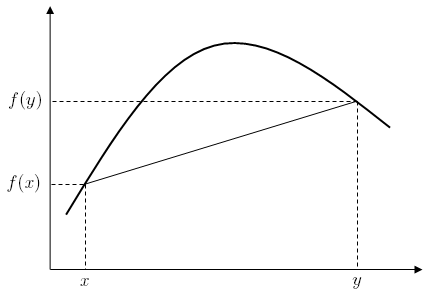

A function is convex if the line segment connecting any two points on its graph lies on or above the graph itself. Intuitively, a convex function looks like a "bowl" or a "valley" opening upwards.

Formal Definition¶

A function \(f(x)\) is defined to be convex over an interval \(I\) if for any two points \(x_1, x_2 \in I\) and for any scalar \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\), the following inequality holds:

- Explanation: The term \(\lambda x_1 + (1-\lambda)x_2\) represents any point on the line segment between \(x_1\) and \(x_2\). The left side of the inequality, \(f(\lambda x_1 + (1-\lambda)x_2)\), is the value of the function at this intermediate point. The right side, \(\lambda f(x_1) + (1-\lambda)f(x_2)\), is the value on the straight line (the chord) connecting the points \((x_1, f(x_1))\) and \((x_2, f(x_2))\). The definition essentially states that the function's curve is always below or touching this chord.

Strictly Convex¶

If the inequality is strict (<) for all \(\lambda \in (0, 1)\) and \(x_1 \neq x_2\), the function is called strictly convex. This means the graph is always strictly below the chord, never touching it except at the endpoints.

Concave Functions¶

A function is concave if the line segment connecting any two points on its graph lies on or below the graph. Intuitively, a concave function looks like a "hill" or a "dome" opening downwards.

Formal Definition¶

A function \(f(x)\) is defined to be concave over an interval \(I\) if for any two points \(x_1, x_2 \in I\) and for any scalar \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\), the following inequality holds:

Relationship between Convex and Concave¶

There is a simple relationship between concave and convex functions:

A function \(f(x)\) is concave if and only if the function \(-f(x)\) is convex.

Tests for Convexity and Concavity¶

For functions that are twice differentiable, we can use simple tests involving their derivatives to determine their concavity.

First Derivative Test¶

- If the first derivative \(f'(x)\) is a non-decreasing (i.e., increasing or constant) function over an interval, then \(f(x)\) is convex on that interval.

- If the first derivative \(f'(x)\) is a non-increasing (i.e., decreasing or constant) function over an interval, then \(f(x)\) is concave on that interval.

Second Derivative Test¶

This is the most commonly used and straightforward test. Let \(f(x)\) be a twice-differentiable function on an interval \(I\).

- If \(f''(x) \geq 0\) for all \(x \in I\), then \(f(x)\) is convex on \(I\).

- If \(f''(x) \leq 0\) for all \(x \in I\), then \(f(x)\) is concave on \(I\).

- If \(f''(x) > 0\) for all \(x \in I\), then \(f(x)\) is strictly convex on \(I\).

- If \(f''(x) < 0\) for all \(x \in I\), then \(f(x)\) is strictly concave on \(I\).

Examples¶

Example 1: \(f(x) = x^2\)¶

- First derivative: \(f'(x) = 2x\)

- Second derivative: \(f''(x) = 2\)

- Conclusion: Since \(f''(x) = 2 > 0\) for all real numbers \(x\), the function \(f(x) = x^2\) is strictly convex everywhere.

Example 2: \(f(x) = \log_e(x)\) or \(\ln(x)\) for \(x > 0\)¶

- First derivative: \(f'(x) = \frac{1}{x} = x^{-1}\)

- Second derivative: \(f''(x) = -1 \cdot x^{-2} = -\frac{1}{x^2}\)

- Conclusion: Since \(x^2\) is always positive for \(x > 0\), \(f''(x) = -\frac{1}{x^2}\) is always negative. Therefore, the function \(f(x) = \ln(x)\) is strictly concave on its domain \((0, \infty)\).

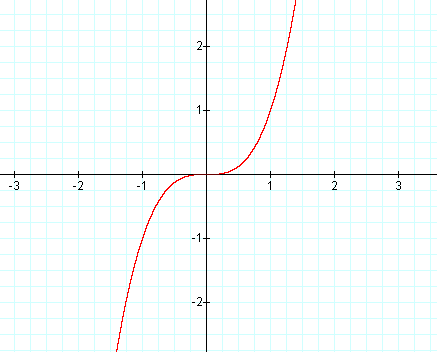

Example 3: \(f(x) = x^3\)¶

- First derivative: \(f'(x) = 3x^2\)

- Second derivative: \(f''(x) = 6x\)

- Conclusion: The sign of \(f''(x)\) depends on the value of \(x\).

- For \(x > 0\), \(f''(x) > 0\), so the function is convex.

- For \(x < 0\), \(f''(x) < 0\), so the function is concave.

- Thus, \(f(x)=x^3\) is neither convex nor concave over its entire domain.

Point of Inflection¶

A point of inflection (or inflection point) is a point on a curve where the concavity changes (from convex to concave, or vice-versa).

- This change occurs at points where the second derivative \(f''(x)\) is either zero or does not exist.

- In the example of \(f(x) = x^3\), we saw that \(f''(x) = 6x\). Setting \(f''(x) = 0\) gives \(x=0\). At \(x=0\), the function changes from concave to convex. Therefore, the point \((0, f(0)) = (0, 0)\) is a point of inflection.

[insert image on graph of y = x^3 showing inflection point]

Significance in Optimization¶

Concavity is a cornerstone of mathematical optimization, a field with wide applications in computer science, machine learning, and economics.

- Convex Functions: For a convex function, any local minimum is guaranteed to be a global minimum. This property is extremely useful because it means optimization algorithms won't get "stuck" in a suboptimal valley.

- Concave Functions: Similarly, for a concave function, any local maximum is guaranteed to be a global maximum.

- Convex Optimization: Problems that involve minimizing a convex function (or maximizing a concave function) over a convex set are known as convex optimization problems. These problems are considered efficiently solvable, and many complex real-world problems are modeled in this form to find a guaranteed optimal solution.

Problem Set¶

This problem set contains 60 questions covering the core concepts of functions, mathematical induction, and convex/concave functions, designed for BCA-level understanding.

Functions¶

Definition and Properties of Functions¶

- Define a function. What are the three essential components of a function? Provide an example.

- Explain the "well-defined" property of a function. Which of the following relations \(R\) from \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) to \(B = \{a, b, c\}\) are functions? Justify your answer.

- \(R_1 = \{(1, a), (2, b), (3, c)\}\)

- \(R_2 = \{(1, a), (2, b)\}\)

- \(R_3 = \{(1, a), (2, b), (1, c)\}\)

- \(R_4 = \{(1, a), (2, a), (3, a)\}\)

- Let a function \(f: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}\) be defined by \(f(x) = x^2 + 2\). Determine the domain, codomain, and range of \(f\).

- Consider the function \(f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4-x^2}}\). What is the largest possible subset of \(\mathbb{R}\) that can be the domain of this function?

- If \(A = \{-2, -1, 0, 1, 2\}\) and \(f: A \to \mathbb{R}\) is defined by \(f(x) = x^3 - x + 1\), find the range of \(f\).

One-to-One (Injective) Functions¶

- Formally define a one-to-one (injective) function.

- Prove that the function \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x) = 5x + 3\) is injective.

- Show that the function \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x) = x^2 - 1\) is not injective.

- Is the function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\) defined by \(f(n) = n^2 + 1\) one-to-one? Justify your answer.

- Let \(A = \mathbb{R} - \{1\}\). Check if the function \(f: A \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x) = \frac{2x+3}{x-1}\) is injective.

- Give an example of a function from \(\mathbb{Z}\) to \(\mathbb{Z}\) that is not one-to-one and explain why.

- If \(f: A \to B\) and \(g: B \to C\) are both injective functions, prove that their composition \(g \circ f: A \to C\) is also injective.

Onto (Surjective) Functions¶

- Formally define an onto (surjective) function.

- Prove that the function \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x) = x^3\) is surjective.

- Show that the function \(f: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}\) defined by \(f(x) = 2x + 1\) is not surjective.

- Determine if the function \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x) = x^2 - 2x + 1\) is onto. Provide a clear justification.

- Let the codomain be restricted such that \(f: \mathbb{R} \to [4, \infty)\). Is the function \(f(x) = x^2 + 4\) surjective in this case? Explain.

- Give an example of a function from \(\mathbb{N}\) to \(\mathbb{N}\) that is not onto and explain why.

- If \(f: A \to B\) and \(g: B \to C\) are both surjective functions, prove that their composition \(g \circ f: A \to C\) is also surjective.

Bijective Functions¶

- Define a bijective function. What is another name for a bijective function?

- Prove that \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(x) = 2 - 3x\) is a bijection.

- Let \(f: \mathbb{R} - \{2\} \to \mathbb{R} - \{5\}\) be defined by \(f(x) = \frac{5x+1}{x-2}\). Show that \(f\) is bijective.

- Find the inverse, \(f^{-1}(x)\), of the bijective function from the previous problem.

- Show that the function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}\) defined by \(f(n) = (-1)^n \lfloor n/2 \rfloor\) is a bijection.

- Determine if the function \(f(x) = x|x|\) is a bijection from \(\mathbb{R}\) to \(\mathbb{R}\). Justify your conclusion.

Principles of Mathematical Induction¶

The First Principle (Weak Induction)¶

- State the First Principle of Mathematical Induction, outlining the base case and the inductive step.

- Using mathematical induction, prove that for all positive integers \(n\), \(1 + 3 + 5 + \dots + (2n-1) = n^2\).

- Prove by induction that \(1^3 + 2^3 + \dots + n^3 = \left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)^2\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

- Prove that \(n^2 + n\) is an even number for all positive integers \(n\).

- Prove by induction that \(5^n - 1\) is divisible by 4 for all integers \(n \geq 1\).

- Use mathematical induction to prove that \(x^n - y^n\) is divisible by \(x-y\) for all positive integers \(n\).

- Prove that \(1 \cdot 1! + 2 \cdot 2! + \dots + n \cdot n! = (n+1)! - 1\) for all \(n \geq 1\).

- Prove by induction that \(n! > 2^n\) for all integers \(n \geq 4\).

- Prove that \(\frac{1}{1 \cdot 3} + \frac{1}{3 \cdot 5} + \dots + \frac{1}{(2n-1)(2n+1)} = \frac{n}{2n+1}\) for all \(n \geq 1\).

- Prove that a set with \(n\) elements has exactly \(2^n\) subsets for \(n \geq 0\).

- Prove that for any \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), \(11^{n+1} + 12^{2n-1}\) is divisible by 133.

- Prove by induction that \( (1+x)^n \geq 1 + nx \) for all \(x > -1\) and integers \(n \geq 0\) (Bernoulli's Inequality).

The Second Principle (Strong Induction)¶

- State the Second Principle of Mathematical Induction (Strong Induction). How does its inductive hypothesis differ from that of weak induction?

- Use strong induction to prove that every integer \(n > 1\) has a prime factor.

- A sequence is defined recursively by \(a_1 = 1\), \(a_2 = 3\), and \(a_n = 2a_{n-1} - a_{n-2}\) for \(n \geq 3\). Use strong induction to prove that \(a_n = 2n-1\) for all \(n \geq 1\).

- Prove using strong induction that any postage amount of 12 cents or more can be formed using only 4-cent and 5-cent stamps.

- The Fibonacci numbers are defined by \(F_0 = 0, F_1 = 1\), and \(F_n = F_{n-1} + F_{n-2}\) for \(n \geq 2\). Prove that \(F_n < 2^n\) for all \(n \geq 0\).

- A sequence is defined by \(c_0 = 1, c_1 = 2, c_2 = 3\) and \(c_k = c_{k-1} + c_{k-2} + c_{k-3}\) for \(k \geq 3\). Prove using strong induction that \(c_n \leq 3^n\) for all \(n \geq 0\).

- Consider a game where two players start with a pile of \(n\) stones and take turns removing 1, 2, or 3 stones. The player who removes the last stone wins. Prove that the first player has a winning strategy if and only if \(n\) is not a multiple of 4.

- In what scenarios is strong induction necessary or more convenient than weak induction? Provide an example.

Convex and Concave Functions¶

Definitions and Tests¶

- Define a convex function and a concave function using the formal definition involving a line segment.

- What is the relationship between a convex function \(f(x)\) and the function \(g(x) = -f(x)\)?

- State the Second Derivative Test for determining intervals of convexity and concavity.

- If the first derivative, \(f'(x)\), of a function is increasing over an interval \((a, b)\), what can you conclude about the convexity of \(f(x)\) on that interval?

- Show that \(f(x) = x^2\) is a strictly convex function on \(\mathbb{R}\) using the second derivative test.

- For \(x > 0\), determine if the function \(f(x) = \sqrt{x}\) is convex or concave. Justify your answer.

- Determine the intervals on which the function \(f(x) = x^3 - 3x^2 + 1\) is convex and concave.

- Find the intervals of convexity and concavity for the function \(f(x) = \frac{x}{x^2+1}\).

- Show that \(f(x) = \ln(x)\) is a strictly concave function for \(x > 0\).

- Analyze the convexity of the function \(f(x) = x e^{-x}\) for \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Point of Inflection and Applications¶

- What is a point of inflection? What condition must the second derivative typically satisfy at a point of inflection?

- Find all points of inflection for the function \(f(x) = x^4 - 6x^2\).

- Find the point(s) of inflection for the function \(f(x) = (x-2)^3\).

- Does the function \(f(x) = x^4\) have a point of inflection at \(x=0\)? Explain why or why not, considering \(f''(0) = 0\).

- Briefly explain the significance of convexity in optimization problems. For example, what does strict convexity of a function guarantee about a point where \(f'(c) = 0\)?